Diseases in the developing world cause an enormous amount of suffering. Controlling them requires vast sums of money. Could funding the development of a vaccine, ending the problems caused by the specific disease once and for all, be an immensely cost-effective way to donate? The case for this type of charitable giving is obvious: giving money to people doing this research and development (R&D) will lead to an earlier vaccine-day (the time at which a working vaccine is ready for service). Bringing forward this point by even a day could prevent a serious number of DALYs from being inflicted. We've been looking at a few ways we could model the cost-effectiveness of funding a general vaccine development charity. This post will explore the first of these models.

The Sabin Vaccine Institute is a good example of this type of charity. Sabin is conducting non-profit R&D for a number of different neglected disease vaccines, but GWWC are particularly interested in their work on schistosomiasis (also knows as bilharzia, bilharziosis or snail fever), a vacc ine for which is scheduled to enter phase 1 clinical trials next year. The aspiration of this series of blog posts will be to get a reliable cost-effectiveness estimate of donations to this schistosomiasis vaccine development program.

To begin with we’ll assume that a vaccine will definitely be produced eventually, either by the program we donate to or by a different one. Then with any model there's a natural way to split the calculation up into 2 parts. Firstly we want to know just how much our donation will bring forward V-day. Secondly we want to find out how bringing forward this momentous occasion by 1 unit of time translates to positive effects in the developing world (measured in DALYs). Then we’ll combine these to get a figure for positive effect per donation.

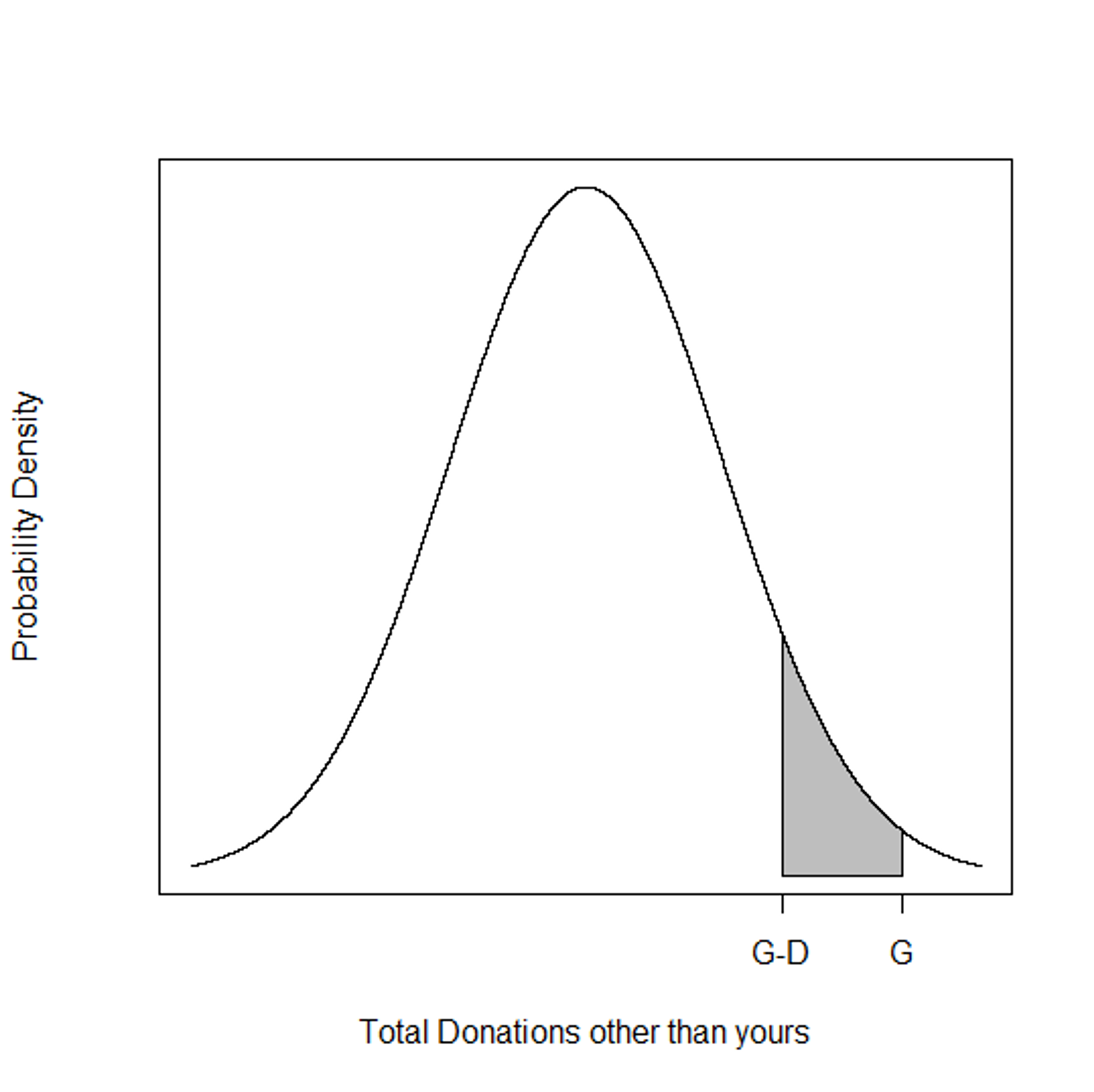

So how much will our donation affect V-day? Say the charity is at a certain stage of its research, and plans to begin its next stage at some particular point in the future if they fill up a funding pot, of size G. If not, they will postpone to another date T years after the first date. We’re only concerned with whether my donation (of size D) makes the difference between the research going ahead and being postponed; so how effective we think it is to donate will depend a lot on how much we think the charity will fundraise elsewhere. If we think that they'll fill their pot and then some, or that everyone else will stay away, then it’s unlikely my donation will make much difference to the outcome. The problem of course is that we don't know how much everyone else is going to donate! To get around this we can try to estimate a distribution of how much we think everyone else will give in total. Plausibly, the total amount donated (excluding our donation) is distributed normally [The reason for this is that F is the sum of lots of other people’s donations. Assuming (for simplicity) that the individuals' donations choices are independent, the central limit theorem says that their sum will be approximately normal]. In that case, the probability that our donation will make a difference is P[G - D < F < G]; this is the probability that the total amount donated (excluding our donation) will be within D of filling the funding pot, so that our donation fills the pot (this probability is represented by the grey area in the graph below). So our expected time impact on V-day will be P[G - D < F < G]Tp where p is the probability that the program successfully produces a vaccine (If the program fails to produce a vaccine then our funding has not brought forward the usage of any vaccine, and unfortunately, many vaccine projects do fail.)

Now for part 2! There are 2 important positive effects which might come from having a vaccine available earlier.

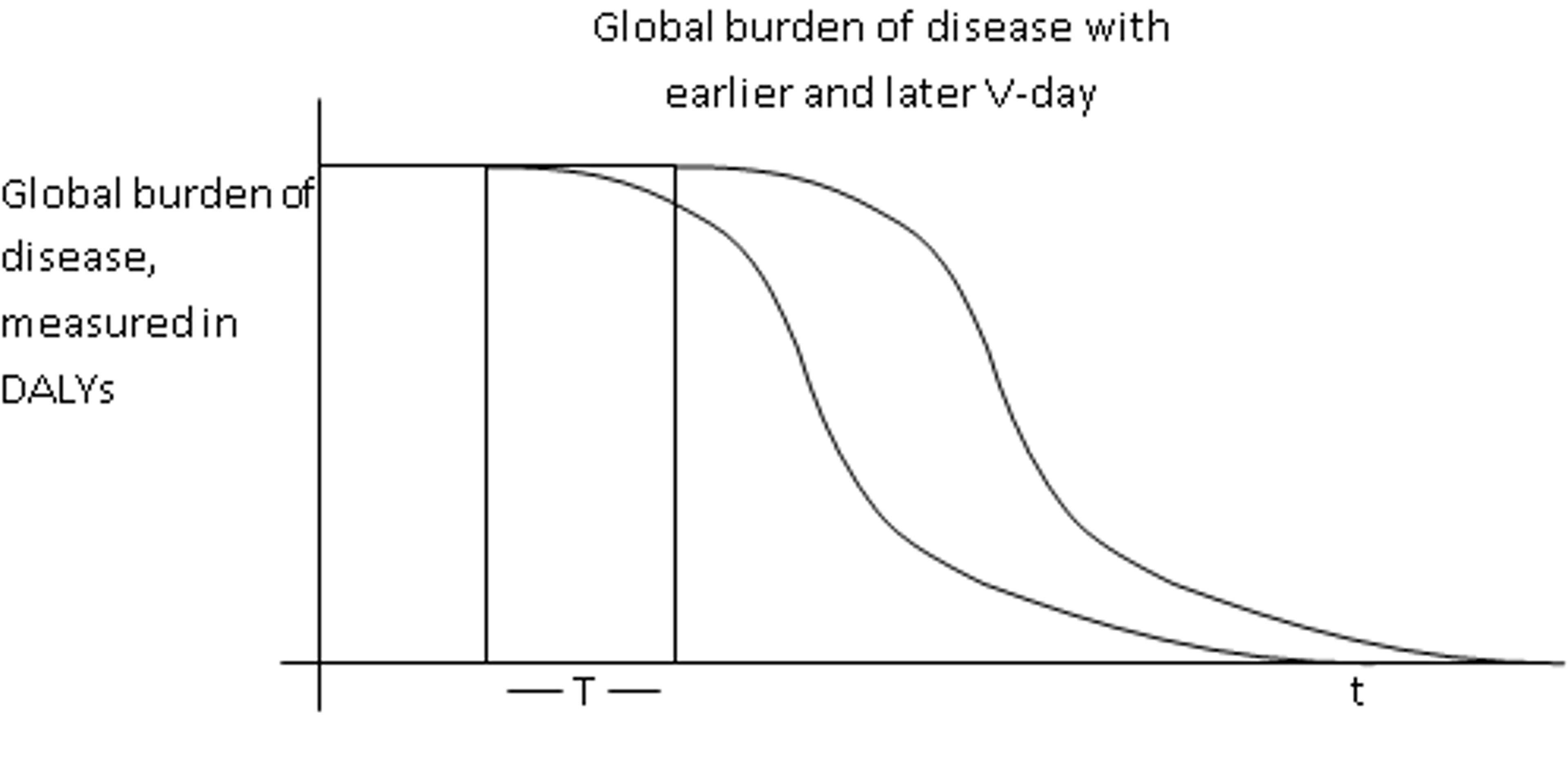

Firstly people who are at risk from the disease will benefit from the vaccine being ready to use earlier. For the moment we'll assume that eradication is achieved exactly T years earlier if the vaccine is successfully developed without the delay in research due to lack of funding. (There are possible reasons why this might not be true, for example that the vaccine might not be the limiting factor in the eradication effort). Assuming that eradication is achieved eventually in all cases and happens in the same way whenever the eradication effort begins then by looking at the graph below we can see that our impact depends on the global burden of disease (DALYs caused by the disease annually) between T1, the time at which the vaccine will be ready if funding is reached, and T2, the time at which the vaccine will be ready if the next stage of development is delayed due to lack of funding. So if the GBD of the disease is B DALYs/year then the expected benefit of our donation is the expected time impact of our donation multiplied by B. This is B* P[G - D < F < G]Tp DALYs.

The second benefit is because the annual cost of controlling a disease could be massive. If we assume that the money being spent on control would otherwise be diverted to other health interventions in the developing world then potentially this would avert vast numbers of DALYs. Let the cost of controlling the disease be $C/year. If the average cost-effectiveness of health interventions in the developing world is X DALYs/$ then for each dollar diverted the benefit is CX DALYs/year. Therefore multiplying as before gives expected benefit of our donation due to diverted dollars as CX*P[G - D < F < G]Tp DALYs.

Thus our first basic benefit estimate for a donation of size D to a vaccine development charity is the sum of the 2 benefits of our donation, (B+C*X)*P[G - D < F < G]Tp DALYs. Assuming some fairly conservative numbers for the inputs and the parameters of the distribution of funding suggests that vaccine charities have the potential to be quite cost effective.

There is a other factors still to be taken into consideration. For instance, some vaccines are only partially effective and some diseases might be controlled by other means before a vaccine is developed. Allocating scarce biomedical researchers to vaccine research will take them away from other R&D programs. In future blog posts, as we explore some other models, we hope to find some ways to deal with these things.