Is climate change the world’s biggest problem? And what can we do about it?

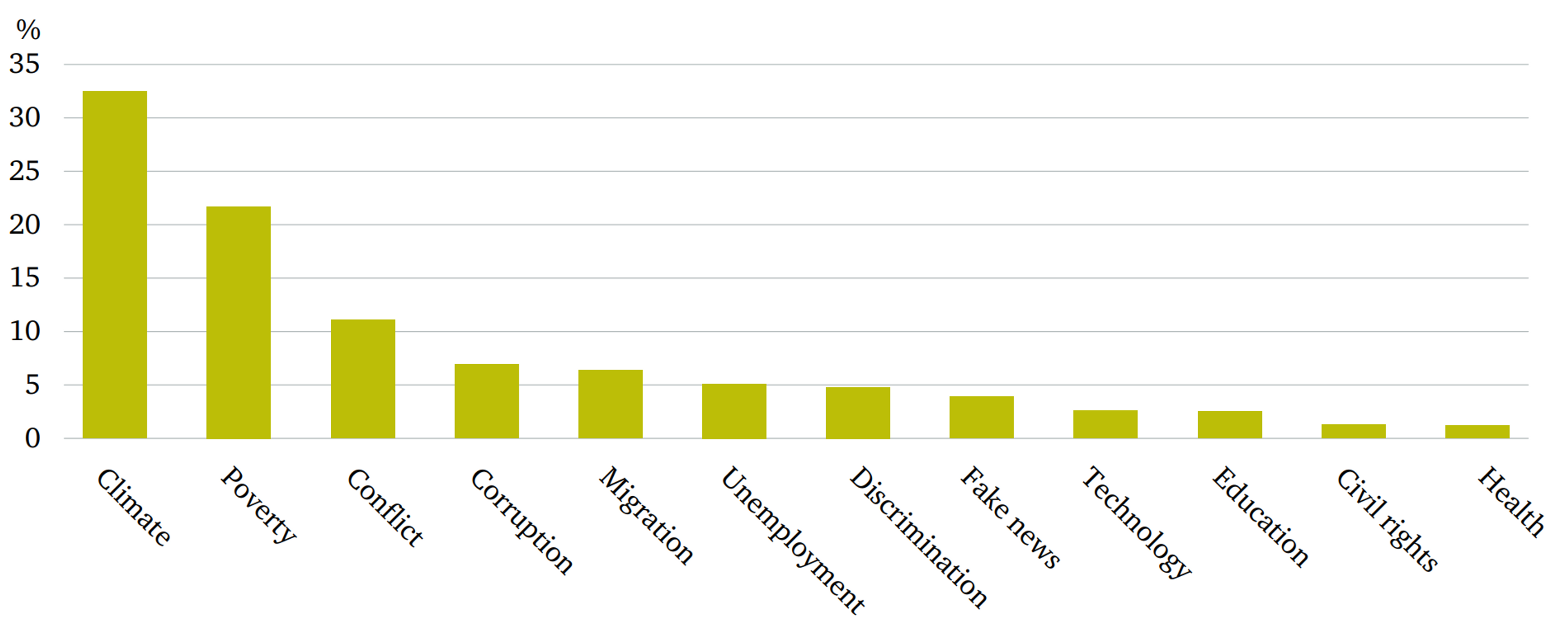

When thousands of young people were asked what they thought the world’s biggest problem was in 2019, climate change was the most common answer.

In this executive summary, we investigate three questions:

- Are these young people right? Is climate change the world’s biggest problem?

- What are the best available solutions?

- If you want to combat climate change, which charities should you support?

First, let's discuss what climate change is.

What is climate change?

Human-induced climate change began at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution with James Watt’s patent for the steam engine in 1769. The Industrial Revolution led to the first sustained increase in average living standards for millennia, but also centuries of almost unchecked fossil fuel burning.

Greenhouses gases like CO2 and methane trap heat heading out from the Earth, leading to warming. Since the Industrial Revolution, average global temperatures have increased by around 1°C, with most of the warming coming after 1980.

Each time you drive your car, a sizeable fraction of the CO2 you release will stay in the atmosphere for millennia. If current trends continue, by the end of the century, CO2 concentrations and global temperatures will be higher than they have been for tens of millions of years.

Already, climate change has led to rising sea levels that threaten island nations and coastal cities, caused a higher occurrence of catastrophic weather events, and thereby made the world a more hostile place to live in. And burning fossil fuels not only causes climate change, but also kills millions of people every year via air pollution.

Given this, it’s no surprise that young people today are concerned — and they’re right to be. But in the survey of young people cited above, two thirds of the respondents considered something other than climate change to be the world’s biggest problem. So, who’s right?

1. Is climate change the world’s most pressing problem?

It’s important to note at the outset that being “the world’s biggest problem” is a very high bar, and it’s much more difficult to answer than the simpler question of whether climate change is worth addressing at all (the answer: it is).

But it’s the question we’re asking, because if you’re trying to do the most good you can do, it’s worth prioritising the most important problems first.

Sadly, there’s plenty of competition for climate change to face to be considered the world’s biggest problem. Billions of animals suffer each year in horrendous conditions, millions of human lives are lost to preventable diseases, and there are major risks to our survival as a species, like catastrophic biological events and powerful artificial intelligence that is not aligned with humanity.

So, how do you work out which is the most important? It’s a nearly (but not-quite!) impossible question to answer. To help, we’ll use a framework that considers three things:

- Scale — How good would it be if this problem were solved?

- Neglectedness — Is the problem getting the response it deserves?

- Tractability — Are there ways of making progress?

You can read more about this framework here.

In addition to this framework, we’re going to look at this problem from two different perspectives: longtermism and neartermism.

Longtermism is the idea that ensuring that the long-term future goes well is a key moral priority. There are roughly three ideas behind it:

- Future people and current people count equally.

- The future could be vast, and contains enormous potential value.

- We can shape this future (for example, by averting catastrophes that would end it or cause enormous suffering).

On this view, it’s especially important to consider how our actions today might have very long-term consequences. This makes actions that irreversibly change the future, such as extinction, are especially important.

On the other hand, neartermism is the view that we should be especially focused on people or animals alive now or in the foreseeable future. Often, this involves reducing global poverty, or reducing the suffering of factory farmed animals. It’s probably simplest to think of neartermism as a poor label for not-longtermism, as there are many radically different worldviews that could be counted as ‘neartermist.’ What neartermists have in common is that they don’t put such significant weight on how actions affect the very long-run future.

Climate change is important from both longtermist and neartermist points of view, but they differ in which effects of climate change matter most. Our full report, and this executive summary, primarily evaluate climate change as part of our research on safeguarding the long-term future, and therefore focus on the most extreme risks. But we also aim to provide some discussion of climate change from a neartermist perspective.

The first question to ask is: how damaging could climate change be?

Scale — Just how bad could climate change be?

Scale involves considering how big the problem is, and we can break down the scale of the climate change problem into two questions:

- How much warming do we expect?

- How bad would this warming be?

Scientists have been investigating these questions for decades. To answer them, they don’t just have to figure out how to model the climate; they also need to model human beings: how will our behaviour change in the face of this ongoing crisis? Given this complexity, it’s impossible to expect concrete answers to these questions. Instead, we’re going to have to grapple with uncertainty. In that spirit, we’ll consider the scale of climate change in terms of the most likely outcome and the worst-case scenario.

With that in mind, let’s turn to the first question.

How much warming do we expect?

Due to extraordinary progress on renewable energy sources and batteries, combined with increasingly stringent global climate policy, it now looks as though the most likely outcome follows what the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) calls a “medium-low” emissions pathway: 2.5–3°C of warming in 2100, relative to pre-industrial levels. There is even some evidence that these studies might be too pessimistic because they underestimate likely progress on renewables, batteries, and other technologies, and do not account for existing targets and stronger climate policy in the future.

What about a worst-case scenario? This would involve burning through all of the fossil fuels,1 which is unlikely but not impossible. This could happen even if we decarbonise substantially but not completely — for example, if emissions fall to a quarter of their current levels, then we would burn through all of the recoverable fossil fuels in about 750 years. If we did, there would most likely be around 7°C of warming relative to the pre-industrial period, and a 1-in-6 chance of warming of more than 9.5°C.2

So, under the most likely outcome, we look set for around 3°C of warming by 2100, but in the worst case, there would be more than 7°C of warming.

How bad would this warming be?

In what follows, we focus on what we see as the most important humanitarian consequences of climate change:

- Tipping points — could climate change make the Earth uninhabitable?

- Agricultural impacts — could climate change prevent us from feeding ourselves?

- Indirect effects — could climate change make the world hostile, or increase the risk of other threats to humanity?

There are also many other negative effects that we do not consider here, such as rising sea levels, loss of biodiversity, and reduced labour productivity. But we chose the above three because they are especially important from a longtermist perspective: each bears on whether climate change might cause us to go extinct, or cause a major global catastrophe with long-lasting consequences. And though neartermists might put less weight on these considerations, they’re still important from a neartermist perspective. In future work, we’d like to explore how these other effects may change our analysis of the severity of climate change.

1. Tipping points

A ‘tipping point’ refers to some threshold that might — when exceeded — cause a sudden, substantial, and potentially irreversible change to the climate. This could be devastating for humanity. As an example, Venus may have once been the home of vast oceans, but it experienced the runaway greenhouse effect and so, simply put, boiled away. To add a bit more detail: essentially, the Sun’s heat may have gradually boiled away Venus’s oceans, and as this occurred, the ocean’s water vapour (which forms a ‘greenhouse’ that protects the planet against the Sun) diminished, leading to further heating and evaporation. This may have continued until Venus arrived at its current state: barren and uninhabitable.

Could we become like Venus, where we reach a tipping point where the Earth’s warming leads to even further warming, which continues until the oceans are gone?

The short answer is no. A tipping point this extreme is, according to our current scientific understanding, impossible (see our report’s discussion on this).

But there are other less extreme tipping points to consider, some of which are particularly concerning:

- Rapid warming and regional droughts.

- A collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (a major current system in the world’s oceans which plays a crucial role in regulating the climate).

- Changes in monsoons.

We discuss these in our full report, but there is also excellent discussion in this article by Carbon Brief. The bottom line is that some tipping points are plausible, and worrying.

So, the climate is somewhat unstable and may change: could this be the end of humanity? We think this will largely depend on whether we will continue to be able to produce enough food to survive.

2. Agricultural impacts

Overall, both the most likely and the worst-casescenarios look set to have damaging effects on agriculture. In our full report, we explore in more detail how these scenarios may affect crop yields, soil moisture, and the productivity of agricultural workers, but here we will just give our conclusion: we likely will be able to survive.

There are several reasons for this:

- Overall, climate change will make agriculture (potentially much) more difficult, but it would also have some positive effects on agriculture by freeing up frozen land at higher latitudes.

- Though our crop yields will suffer, we will likely be able to continue the trend of adapting our agriculture to maintain food production even in more hostile climates.

- It provides some comfort that agricultural capacity to date has actually increased, even with rising temperatures.

All in all, it looks like low-income countries in the tropics could be hit hard by the agricultural effects of climate change, but that the most likely effects will fall well short of global food catastrophe (i.e., something that could kill upwards of 10% of the global population). This is still terrible, and warrants significant action, but does provide some assurance in terms of how climate may affect humanity’s long-term future.

However, lower-probability tipping points could do much more damage. Most importantly, if there were an abrupt collapse in the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, temperatures would decline by 3–5°C in the Northern Hemisphere (though there would be a warmer starting point due to climate change). Cooling is generally much worse for crops than warming, because one day of frost destroys the entire growing season. Yet, this would not make it impossible for humanity to continue to feed itself. For example, Britain would experience some of the most dramatic climatic effects, but would be able to offset a lot of the impact by using irrigation. Whether poorer countries would be able to adapt to the changes in rainfall patterns is less clear — the humanitarian consequences could be severe.

Though food shortages are the most plausible direct path that climate change could cause catastrophic damage, there are several indirect ways climate change could cause disruption that need to be considered.

3. Indirect risks

Climate change could also indirectly increase risks, such as conflict and political instability.

The effect of climate change on conflict to date is controversial. Some studies suggest that climate change has caused increased levels of civil conflict in Africa, but there is consensus in the literature that it has so far been a small driver relative to other factors such as low per capita income and states’ low capacity to govern effectively.3

It is hard to say what the effect on conflict would be in the worst-case scenario, as this is far outside of lived human experience — there are no strong historical or contemporary case studies we can turn to. If poor agrarian countries do start to experience serious agricultural disruption, droughts, or flooding, that might lead to political instability and damage international coordination. Indirect risks such as this are difficult to quantify, but plausibly account for a substantial fraction of the global catastrophic risk from climate change.

The most important potential future conflict is war between the great powers, including the US, China, India, and Russia. Though a few scholars have raised climate change as an important driver of this conflict, other factors (such as the shifting global balance of power) seem much more important.

So, now we’ve taken a look at climate change’s scale — which in brief is massive, but unlikely to end humanity. But whether we should prioritise a problem does not just depend on how significant it is; we need to also consider how feasible it is to solve it.

Tractability — How hard is it to address climate change?

Compared to other risks to humanity, climate change is one of the most tractable — it is extremely well studied, and there are plenty of promising solutions available.

Firstly, there is a clear success metric for climate change: we know we are winning if we reduce carbon emissions. Compared to other problems like AI safety, nuclear security, and biosecurity, it is much clearer whether we are making progress on climate change.

Secondly, because success is relatively easy to measure, it is easier to identify the most promising ways forward. There are now several climate success stories which suggest that progress on climate change is possible if efforts are carefully designed. For example:

- In the 1970s and 1980s, several countries decarbonised their electricity systems by rapid build-out of nuclear power.

- Since 2007, per-person emissions have fallen by a third in the UK, thanks to advances in energy efficiency and replacing coal with gas, wind, and biomass.

Because climate change has such a clear success metric and different solutions are now so well tested, it is one of the more tractable major global risks.

Though when viewed from a neartermist perspective, we need to compare the tractability of climate change to causes like global health and development and improving farmed animal welfare. Unfortunately, these are more difficult to compare. We haven’t yet fully explored this issue, but it is something we are very interested to investigate in another report.

Neglectedness — Is there room for more work to make a difference?

When we are deciding how to make the biggest impact on the margin, it is important to consider how neglected the problem is: how many resources are already going towards the problem, and how effectively are those resources allocated? Problems that are more neglected still have low-hanging fruit, and diminishing returns have not set in.

Climate change is clearly more neglected than it should be. However, other causes and global catastrophic risks discussed in the effective altruism community are even more neglected. Each year, hundreds of billions of dollars are spent on climate change by governments and the private sector. In recent years, philanthropic spending on climate change has also increased significantly: in 2021, around $5 to $10 billion USD was spent on climate philanthropy worldwide. Spending on other global catastrophic risks is 10–100 times lower than this.4

Still, given that climate change mitigation is a vast cause area that covers the entirety of global economic activity, it would be a mistake to assume that increased climate funding means there are no neglected spaces anymore (see our discussion on this below). And perhaps more importantly, even despite how neglected many other causes are, there are several large funders (such as Open Philanthropy and the Future Fund) that are interested in trying to fund the “low-hanging fruit” in these other areas.5 This makes these areas much less neglected than they would otherwise be (which is a good thing!).

All things considered: Is climate change the world’s most important problem?

Taking into account scale, neglectedness, and tractability, climate change overall is one of the most pressing problems in the world — it is clear that society should put much more effort into fixing it.

From a longtermist point of view, while other problems are more severe and neglected (such as risks from advanced artificial intelligence or biosecurity), climate change’s higher tractability makes it a compelling problem to work on. Also, because so many resources are going into climate change, we can have significant leverage by affecting how these resources are allocated — indeed, we see this as the primary pathway to high cost effectiveness in climate philanthropy (see below).

Nonetheless, both authors of our full report currently believe that biosecurity and promoting beneficial AI are more promising for donors who are neutral across causes and seeking to have the greatest long-term impact.

It is much harder to say how climate change compares to other cause areas from a neartermist point of view. This is an active area of research for effective altruism research organisations, and we are likely to know more in the next few years.

We think working on climate change is robustly good — from multiple perspectives, it seems like a high priority, and this may be especially appealing to readers who are uncertain about their own values and worldviews. There’s substantial evidence and research supporting the conclusion that we ought to be doing more. Now, let’s consider what exactly we ought to do.

2. How can we best address climate change?

For those who want to prioritise climate change, we need to ask: what’s the best way to make a difference?

In this section, we’ll aim to answer that question by establishing a framework for how to think about climate impact, and then highlight three solutions that we think look particularly promising using that framework.

The framework: Four key facts to consider

We suggest that there are four key facts to consider when evaluating approaches to climate change. Let’s look at each in turn, and discuss their implications.

The West accounts for a declining share of emissions

To see this, look at the following graph from Our World in Data:

The US and the EU are expected to contribute at most about 15% of emissions in the 21st century. So, if we are going to avoid the worst-case outcomes, we need to find ways to reduce emissions outside the West. This is particularly challenging given energy use is strongly correlated with living standards — there are strong humanitarian reasons to ensure that people can meet their growing energy needs in the future. We therefore need to find solutions that reduce emissions in emerging economies without damaging living standards.

Global coordination on climate change is difficult

Emissions reduction is a global and intergenerational public good: each country captures only a fraction of the benefits of cutting their emissions. As a result, countries tend to underinvest in emissions reduction. To add to this, regulation of industries to reduce carbon emissions in one country can simply cause industries to move, thereby leaving the total emissions the same. As a result, we think it may be best to focus on solutions that do not rely on extensive global coordination — not because coordination wouldn’t be good, but because it’s very challenging to make happen.

Public and private spending dwarfs philanthropy

Philanthropic spending on climate change is 100 to 200 times lower than public and private spending. This means that climate philanthropy can have significant leverage by focusing on the most effective interventions to improve the response of governments and the private sector.

Philanthropic spending on climate change neglects certain key sectors

By and large, climate philanthropists’ attention is not currently where future emissions are — some key sources of future emissions remain severely neglected. Founders Pledge’s report contains a chart highlighting the distribution of climate philanthropy by region and sector. While there is relatively more funding across a variety of sectors in the US and EU, funding is still far from balanced — it’s heavily tilted towards electricity and electrified transport, and neglects the hardest challenges most in need of additional effort (such as industry, transport, carbon removal, and agriculture). Therefore it may be most impactful to prioritise spending on these neglected sectors.

Our top three solutions

In our full report, we analyse 10 solutions to climate change. Here, we just highlight our top three:

- Clean energy innovation for neglected technologies

- Avoiding carbon lock-in in emerging economies

- Policy leadership

Let’s look at each.

Clean energy innovation for neglected technologies

One especially promising approach to climate change (as identified by Founders Pledge and Let’s Fund) is to focus on clean energy innovation. The great virtue of innovation in low-carbon energy is that it has potential to impact emissions in the sites of future energy demand, but does not require cooperation.

This theory of change can be summarised as follows:

Gigaton impact (massively improving the world!) is the end goal. Even under quite conservative assumptions, this type of advocacy can be highly cost effective due to the leverage of advocacy and global technology spillovers. The benefits are especially large for neglected low-carbon technologies for the reasons discussed in the full report.

While support for solar, wind, and electric cars has been a major success story, certain other key technologies — such as nuclear power, zero-carbon fuels, carbon capture and storage, enhanced geothermal systems, and energy storage are lagging behind.

There are some objections to this approach (discussed in the full report), but on balance we still think it is one of the most promising solutions to the climate problem.

Avoiding carbon lock-in in emerging economies

Carbon lock-in occurs when decisions made today have long-lasting effects via carbon-intensive assets, such as building new coal and steel plants that will last for decades. For example, although the declining cost of renewables affects the prospects for new coal plants, it is much more costly to prematurely retire coal infrastructure that has already been built. This is one key reason to try to avoid building new fossil fuel infrastructure in emerging economies.

As of 2022, Founders Pledge’s climate research team thinks that this is likely one of the highest-impact theories of change, and will continue to do more research and grantmaking in this area.

Policy leadership

One promising philanthropic strategy is to advocate for effective policy leadership: if one country can effectively reduce emissions at reasonable cost and without political backlash, that could be an example that other countries could follow.

Because each country’s emissions are small compared to global emissions and countries constantly copy policies from each other, it may be highly impactful to push for policies in countries in the hope that they will spread globally — even if emissions reductions in the initial country would be low.

Two recent successes illustrate why this approach can be so effective:

- In the 1970s and 1980s, various countries (including Sweden and France) rapidly decarbonised their electricity systems by deploying nuclear power at a large scale, while maintaining low electricity prices.

- In the UK, thanks to a pragmatic mix of regulations, subsidies, and carbon pricing, emissions have plummeted: coal has disappeared from the grid due to energy efficiency and increasing supply from wind power.

Overall, policy leadership is a promising approach to addressing climate change, provided we can identify tractable solutions that are not already supported by other philanthropists.

3. What are the most effective charities and funds working on climate change?

We think the best place to donate to mitigate the effects of climate change is the Founders Pledge Climate Change Fund.6

The strategy of the Fund is to find and fund the highest-impact opportunities based on the considerations laid out here, focusing on avoiding the maximum amount of climate damage. It does this by analysing neglectedness and theories of change, and making time-sensitive as well as multi-year grants. Individual donors contribute to the Fund, which is then distributed by experts in the field to the most effective projects. (Learn more from this podcast with climate journalist David Roberts or read the report on their grantmaking and theory of change.)

So far the Fund supports four different theories of change:

- Accelerating innovation of neglected technologies

- Avoiding carbon lock-in in emerging economies

- Policy leadership and paradigm-shaping

- Growing promising organisations

The charities that they currently recommend include:

- Clean Air Task Force — A highly effective US- and Europe-based nonprofit that focuses on clean energy innovation in OECD countries. It is currently expanding across the world, helped by a grant from the Climate Fund.

- TerraPraxis — A small UK- and US-based nonprofit that advocates for innovation in neglected low-carbon technology, with a particular focus on nuclear power for solving the most difficult decarbonisation problems (such as decarbonised liquid fuels and large committed emissions from new coal plants in Asia).

- Carbon180 — A US-based nonprofit that advocates for carbon removal technologies and approaches, which are neglected but important solutions in the fight against climate change.

- Future Cleantech Architects — A small European think tank focused on accelerating innovation in hard-to-decarbonise sectors.

Note that it is likely significantly more effective to donate through the Climate Change Fund than to the individual charities. This helps ensure each organisation receives the funding they need, and avoids situations where some organisations are unable to carry out projects due to a lack of funding, while others receive more funding than needed; plus the aforementioned impact benefits of multi-year, incubation, and time-sensitive grants. Learn more about why we recommend using expert-led funds.

Donate to the Climate Change Fund

Conclusion

Climate change is one of the most important problems we’ve ever faced as a species, and even though we’ve had some success, it’s clear that in a more rational world, we would be doing far more.

But is it the most important problem?

From a longtermist perspective that focuses on reducing extinction: we think probably not. From a neartermist perspective, we found it too hard to say.

And in any case, we think it’s plausible that for many readers, given their values, it will be among the most impactful causes they could support through their charitable donations. This especially applies to donors who:

- Value the future of humanity, but disagree with our focus on extinction specifically.

- Generally prefer prioritising problems which we have a strong understanding of how to solve.

Most importantly, we think there are strong opportunities for individuals to make a difference. By supporting the most promising solutions, which are carried out by effective charities, you could have an enormous impact for each dollar donated: it might just be the best opportunity you have to make a difference to climate change.

Where can I learn more?

- You can see our full report.

- You can listen to the 80,000 Hours Podcast episode with Johannes Ackva (one of the authors of the full report and the climate research lead at Founders Pledge).

- Carbon Brief is a great source of information on all things climate.

- Navigating the changing landscape of climate philanthropy — Founders Pledge’s deep dive into the current climate action and philanthropy landscape, and what this means for donors who want to maximise their impact.

- David Roberts’s Volts podcast with Johannes Ackva.

- Climate Change: A Risk Assessment by David King, Daniel Schrag, Zhou Dadi, Qi Ye, and Arunabha Ghosh provides an excellent overview of climate risk.

- The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports cover the scientific consensus on climate change.

Our research

This page is an executive summary written by Michael Townsend. You can read our research notes to learn more about the work that went into this page.

Your feedback

Please help us improve our work — let us know what you thought of this page and suggest improvements using our content feedback form.