What is more costly for society – domestic violence or war? A report released recently by researchers at Oxford and Stanford University argues that, despite much greater coverage in the media, war and civil violence account for less than 5% of the total cost of violence worldwide. The greatest burden instead comes from physical violence against women and children in the home. This has implications for the funding of future interventions against violence in the developing world.

Background

The “Conflict and Violence Assessment Paper”[1] was commissioned by the Copenhagen Consensus Centre (CCC), a think tank working to produce economic cost-benefit analyses of solutions to the world’s biggest problems. The Centre is currently focussed on evaluating proposals for the UN post-2015 Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which will replace the current MDGs at the end of next year.

The current set of MDGs appear to have been largely successful in influencing development aid spending since they were unanimously endorsed by all UN member states in 2000. With up to $700bn of aid predicted to be spent between 2015 and 2030, the upcoming MDGs will have a role in directing very large amounts of money.

Hundreds of suggestions for post-2015 goals and specific targets have already been put forward[2] but most, although worthy, have not been subject to serious cost-benefit analysis. The CCC aims to provide Benefits-to-Cost Ratios (BCRs) for the various options on the table to help decision-makers prioritize the most effective goals.

We have been impressed by the Centre’s research in the past[3] and so far this year they’ve evaluated proposed MDGs around issues including improving education[4] and dealing with population growth.[5] If there turns out to be a high variance in the cost-effectiveness of potential MDGs (as is the case with the cost-effectiveness of ) a small investment in this kind of cause prioritization could end up doing a huge amount of good.[6]

The current cost of violence

The issue of violence has already been a focus in the post-2015 MDG discussion, with a UN panel recently highlighting major conflicts, violent crime, and violence against women and girls as high priority problems.[7] In their assessment paper, James Fearon from Stanford and Anke Hoeffler from Oxford University try to determine what kinds of violence we should try to tackle first.

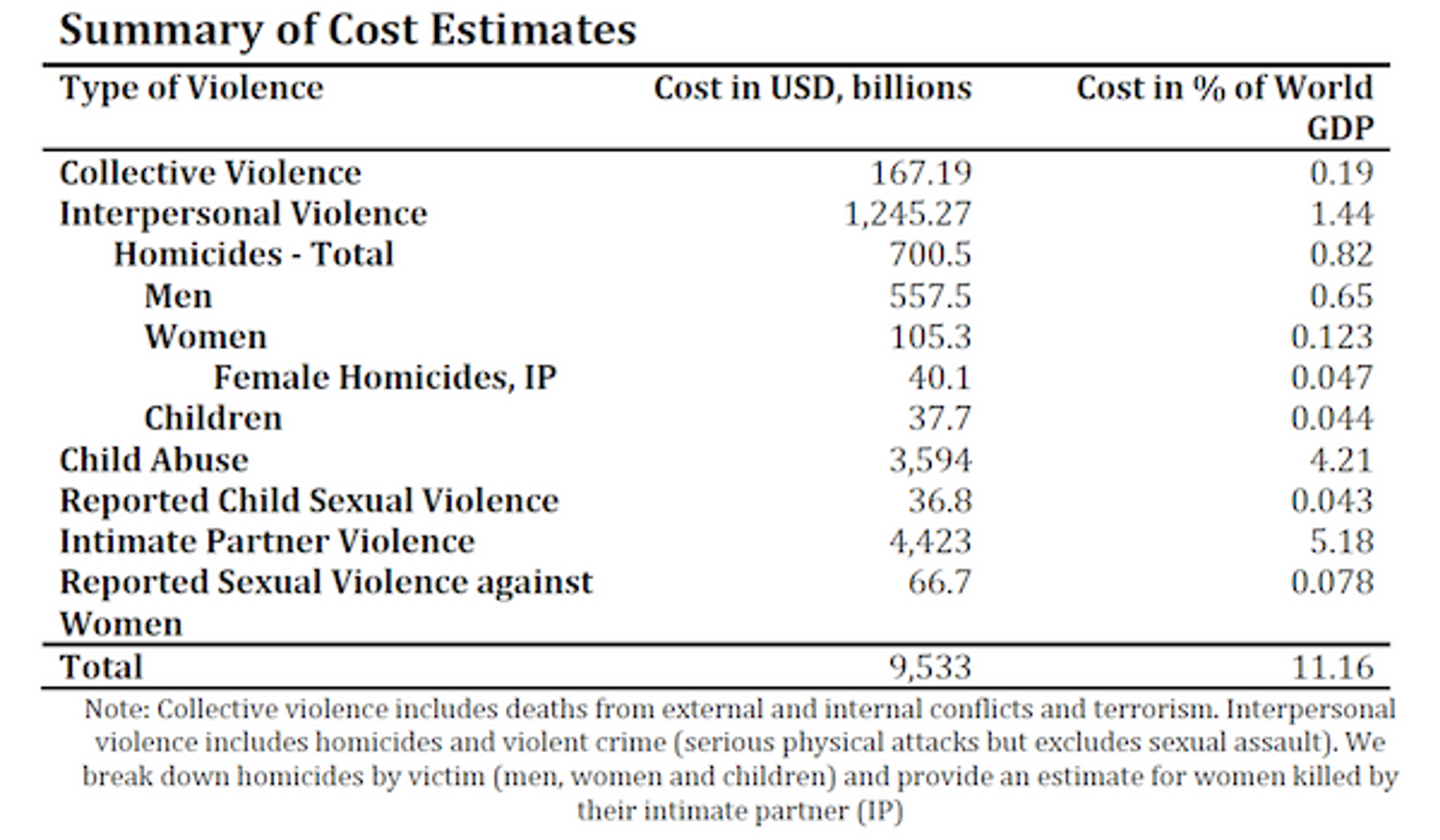

The first step in their analysis is to assign a different “unit cost” to each kind of violent act. This cost represents the average amount of value destroyed by that act in dollar terms. Scaling the unit cost by GDP, and multiplying by the total number of incidents for each act gives the total cost worldwide, expressed as a monetary value or a percentage of global GDP (Table 1).

For example, the unit cost of a single homicide in the US was calculated at $9.1 million, using a model that relates increased wages to increased risk of death across different occupations.[8] Scaling this unit cost by country GDP:US GDP and multiplying by the annual number of homicides for each country[9] gives an estimated global cost of homicide of $700.5 billion USD - 0.82% of world GDP.

A similar approach was used to calculate the total cost of war and terrorism - the total number of war and terrorism-related deaths each year was multiplied by the unit cost for a homicide, and an additional cost was added based on the much larger negative externalities of war compared to homicide (namely, damage to infrastructure and relocation of displaced refugees).

Assigning a unit cost for these forms of violence is slightly more difficult, as their costs are mostly not accounted for in the wage vs. risk-of-death models used previously. Instead, unit cost was calculated by a “jury-compensation” approach that looked at the amount awarded by juries in personal injury cases.[8] Further complicating the calculations was the fact that many forms of non-fatal violence, such as sexual violence against women and children, are widely underreported in both the developed and the developing world. For example, despite the depressingly high worldwide prevalence of domestic (an estimated 30% of all women experience physical or sexual violence from intimate partners in their lifetime[10]), some studies claim that less than 5 percent of this violence is actually reported to the police.[11] Because the authors rely only on reported cases when costing sexual violence against women and children, their costings of these crimes (Table 1) are likely to be underestimates.

To avoid relying on victim reports for child physical abuse, researchers instead estimated prevalence from anonymous surveys on parenting practices.[12] From these data they estimate that 16 percent of all children regularly receive severe physical punishment (labelled Child Abuse in Table 1) , which is defined as “slapping them on the face, head or ears and beating them repeatedly with an implement such as a stick, cane or belt”.[1] Using a unit cost of $95,023 (the cost of a similarly severe assault on an adult), the global cost of child abuse was estimated at $3.59 trillion USD (Table 1).

It is important to note that the total costs reported here do not represent the actual yearly effect of these kinds of violence on global GDP. Rather, they are a way of valuing the welfare costs to the individual and society in objective terms. Another way of think about it is that if all forms of violence (total cost of ~11% GDP) were eliminated tomorrow, it would have a similar effect on human welfare to that of increasing global GDP by 11%.

Table 1. Summary of Cost Estimates Adapted from Hoeffler, Fearson 2014

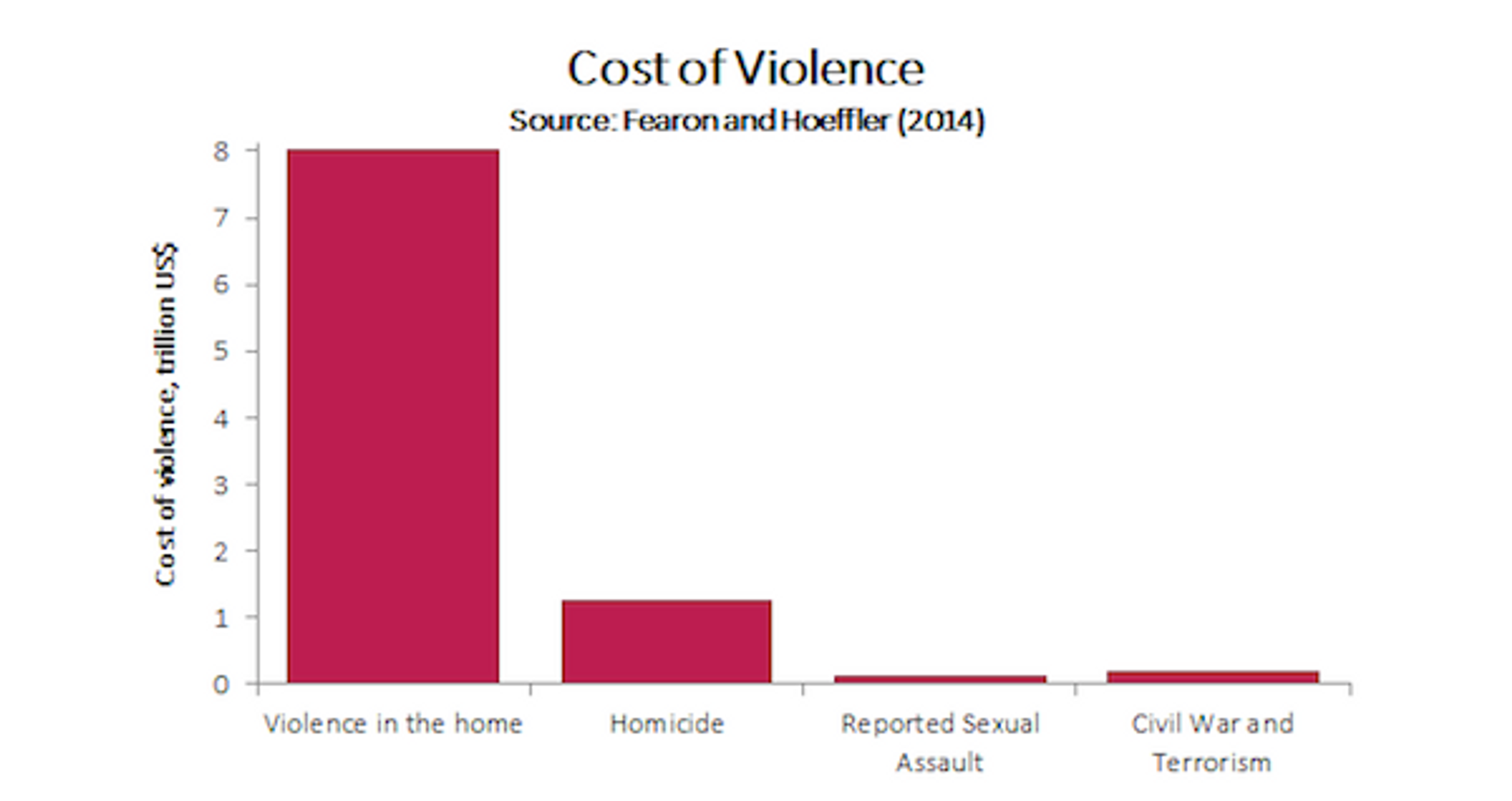

Taken together, the authors estimate that the total cost of violence to the world is approximately $9.5 trillion each year, with domestic violence against women and children making up $8 trillion of that cost. The largest cost is imposed by violence perpetrated against women by their intimate partners, closely followed by physical violence against children (which is predominantly carried out by parents).

Given the relatively small cost of collective violence (including interstate and civil wars, and terrorism), this report makes a good case for increasing the attention we pay to domestic violence and child abuse, which are currently neglected in the global aid budget, and underreported in the media. As Fearson and Hoeffler put it, “[d]omestic abuse of women and children should no longer be regarded as a private matter but a public health concern.”[1] In the next post, we will look at what are the most promising interventions to reduce the cost of violence - stay tuned!

References

- Conflict and Violence Assessment Paper

- The North-South Institute’s Post-2015 Proposal Tracker

- GWWC blog post on the Copenhagen Consensus Centre

- Copenhagen Consensus Centre on Education

- Copenhagen Consensus Centre on Population

- Toby Ord: The Moral Imperative Towards Cost-effectiveness

- [EP: The Economic Cost of Violence Containment](I http://www.visionofhumanity.org/sites/default/files/The%20Economic%20Cost%20of%20Violence%20Containment.pdf )

- The cost of crime to society: New crime-specific estimates for policy and program evaluation

- UN Office on Drugs and Crime: Statistics on homicide, assault, sexual assault and rape

- Science: The Global Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence Against Women

- Tip of the Iceberg: Reporting and Gender-Based Violence in Developing Countries

- UNICEF: The State of the World’s Children 2014 In Numbers