The list of Nobel Peace Prize laureates is a rather extraordinary collection of famous (and infamous) figures whose impact on humanity is undeniable. But many of these people underwent extreme hardship to help others, and it's daunting to think that we could ever emulate them.

However, there are some interventions into global poverty which have, comparatively, quite a low effort to impact ratio (or at least, involve little personal sacrifice). To show this, I have selected a small group of the prize winners who show that all of us, without radically changing our lives, identify such opportunities to help and so change the world for the better.

These are, if you like, the effective altruists of the Nobel Peace Prizes.

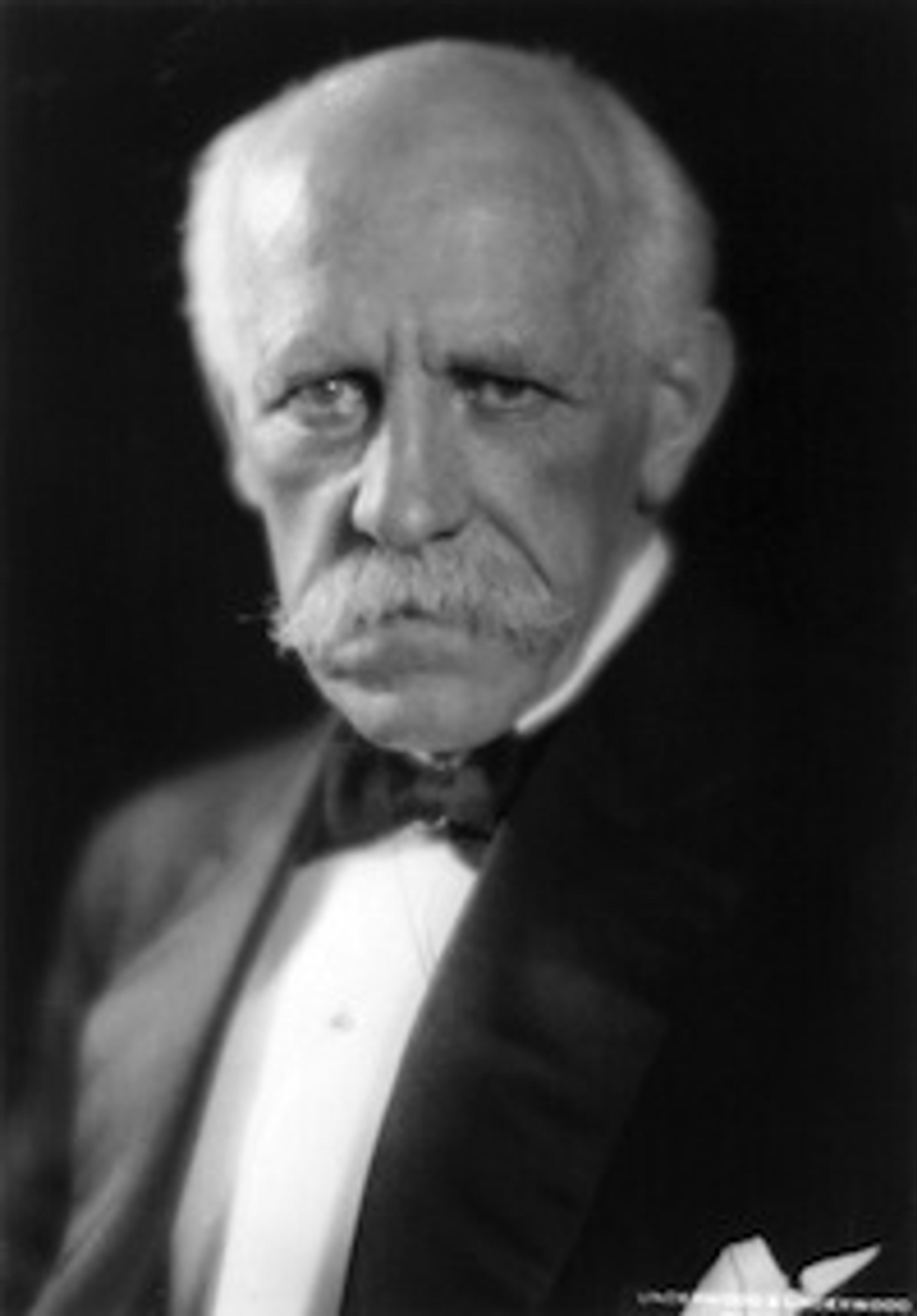

Fridtjof Nansen (1922)

Fridtjof Nansen might be world famous on the basis of his achievements in Arctic exploration, but he's included here for his work with the League of Nations after World War One. Norway maintained neutrality throughout the war, and it's interesting to see how Nansen advocated and achieved Norway's inclusion in the League in 1920, and then to follow his further tireless efforts in the repatriation of post-war refugees and prevention of famine throughout Europe. That included returning 400,000 prisoners to 30 different countries in the immediate aftermath, the successful swap and financial compensation of half a million Greeks and Turks in the aftermath of the Greco-Turk wars, and the eponymous "Nansen passport" which allowed the movement of stateless persons. It was work that the League's Assembly said "would contain tales of heroic endeavour worthy of those in the accounts of the crossing of Greenland and the great Arctic voyage." (ref: Nansen, E. E. Reynolds p. 222-223)Nansen reminds us that we can make a huge difference in situations of extreme poverty that nominally have no relation to us, a idea that Giving What We Can firmly believes in.

Lord John Boyd Orr of Brechin (1949)

One of the basic findings of Giving What We Can has been that the most effective interventions - at least, if we care about giving people more years to live of genuine quality life - involve guaranteeing the basic health of those in extreme poverty. And at least in the UK, no figure has had such an effect on our basic level of nutrition than Lord Boyd-Orr. His research into nutrition found that more than a third of the population of the UK were unable to afford the required amount and variety of food in order to maintain basic health. His research was used to develop the wartime food policy of 1939-45 which, despite rationing, meant that the women and children of poorer classes were healthier at the end of the war than they had been at the beginning. Boyd-Orr was later the first Director General of the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the UN.

Jody Williams (2010) (+ International Campaign to Ban Landmines)

It is estimated that 15,000-20,000 people die every year from landmines, and that approximately 80% of these casualities are children (ref: Walsh & Walsh). Many of the countries with high unexploded landmine count are often also regions of extreme poverty. As chief strategist of the International Campaign to Bad Landmines, Jody Williams' efforts led to the Ottawa Treaty, an international treaty which bans the use of landmines and which has been ratified by most of the world's countries (though notably not Russia, China or the USA). You can see her speak about this, and more broadly about her vision for world peace, here.

Walsh, Nicolas E., and Wendy S. Walsh. "Rehabilitation of landmine victims: the ultimate challenge." Bulletin of the World Health Organization 81.9 (2003): 665-670.

Norman Borlaug (1970)

From a reasonably affluent American background, Borlaug's major scientific achievement was the development of a strain of wheat which was high yield and disease resistant; and his primary humanitarian achievement was the introduction of the crop in Pakistan and India, which were in the mid 1960s falling into famine. Against the background of the Indo-Pakistani war, Borlaug's work counteracted the imminent starvation and brought about the self-sufficiency in wheat production of Pakistan (1968) and India (1974). This has been called the "green revolution" and Borlaug has consequently been credited as the "man who saved a billion lives".

By some metrics - his suffering, the effort the invested, the sacrifices he made - Borlaug ranks pretty averagely with other Nobel Peace Prize winners. But what Giving What We Can seeks to emphasise is that there is no law-like relationship between these metrics and the good you can do. So its worth taking the time to work out what your aim is, and then to carefully assess possible causes to see which best fulfils what you’re interested in. And if what you’re interested in is giving people more years of decent quality life, then I don’t think there is a Nobel Peace Laureate that stands out like Norman Borlaug.

Other inspiring winners

In making the above short list, I set myself two fairly restrictive criteria, so as to keep with the concerns of Giving What We Can: one, that the intervention be clearly beneficial in alleviating the suffering of those in extreme poverty; and two, that the intervention did not require great personal sacrifice (my constraint that it was something we could reasonably aspire to).

Relax the first, and there are a host of distinguished politicians and activists who have campaigned throughout history to resolve specific conflicts, to de-arm nuclear weapons and promote the unity of the world through organisations such as the UN. It's very difficult to assess the effectiveness of these sorts of endeaviours (though the failure of the League of Nations to prevent World War 2 makes it difficult to view Nobel Prizes awarded in relation to the Kellog-Briand Pact as good candidates, say), and researching the effectiveness of charities that advocate political change remains an active area of research at Giving What We Can.

Relax the other, and one thinks of Médecins Sans Frontières, who today fight to guarantee the basic health of Ebola sufferers in Guinea, Sierra-Leone and Liberia, or Malala Yousafzai's campaign for female education in Northwest Pakistan; or the work that the International Committee of the Red Cross or Amnesty International have done to guarantee human rights worldwide.

What I hope to have shown, is that it is possible, often at surprisingly little expense to your own happiness, to make a pretty clear difference in the world. And I hope the insights above - a cost effective nutritious diet, a passport for stateless people, a ban on land-mines, and a high-yield, disease-resistant wheat - offer some fleeting inspiration as to how we might do that.

Images from: Library of Congress, CIMMYT blog, PopperPhoto Getty Images, and Women in Parliaments, respectively.