How flawed judgments limit the impact of charitable donations

People regularly scoff at the mistakes made by charities. We shake our heads at projects that don’t work, or mismanaged charities. But what about us, the donors — how can we improve the effectiveness of our choices?

We think we have a responsibility to make sure that when we are using our wealth to change the world, we're doing the best job we can. But our brains aren’t perfect, and we often make mistakes without even realising it. So how can we overcome that?

To answer this question, there's a lot to learn from Nobel prize winning economist Daniel Kahneman. Throughout his career — most notably in his best-selling book Thinking Fast and Slow — he’s demonstrated that our brains aren’t always good at making the right choices. As he explains it, our brains often make decisions rapidly. That’s a very useful skill! But occasionally, when making those rapid judgments, our brains can easily make mistakes.

Try solving this puzzle without a pen and paper to see what we mean:

A bat and ball cost $1.10. The bat costs one dollar more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?

You probably immediately thought $0.10. But the actual answer is $0.05 (the bat costs $1.05, so together they’re $1.10).

Kahneman outlines all sorts of similar situations in Thinking Fast and Slow, pointing out the many “cognitive biases” — systematic errors in our thinking — that we suffer from.

These biases can lead us to make bad or illogical decisions in all areas of life, without even realising it. But being aware of them can help us recognise them, so we can make an active decision to think "slow" and overcome them. As Kahneman explains, recognising biases is particularly important when the stakes are high — as is the case in philanthropic giving.

Understanding these biases can sometimes allow you to slow down your thinking, which is a very valuable skill when picking charities to support.

So let’s look at four mistakes people make in their judgments about the world — and in the process, help you to make better giving decisions.

1. We're bad at assessing the scale of problems

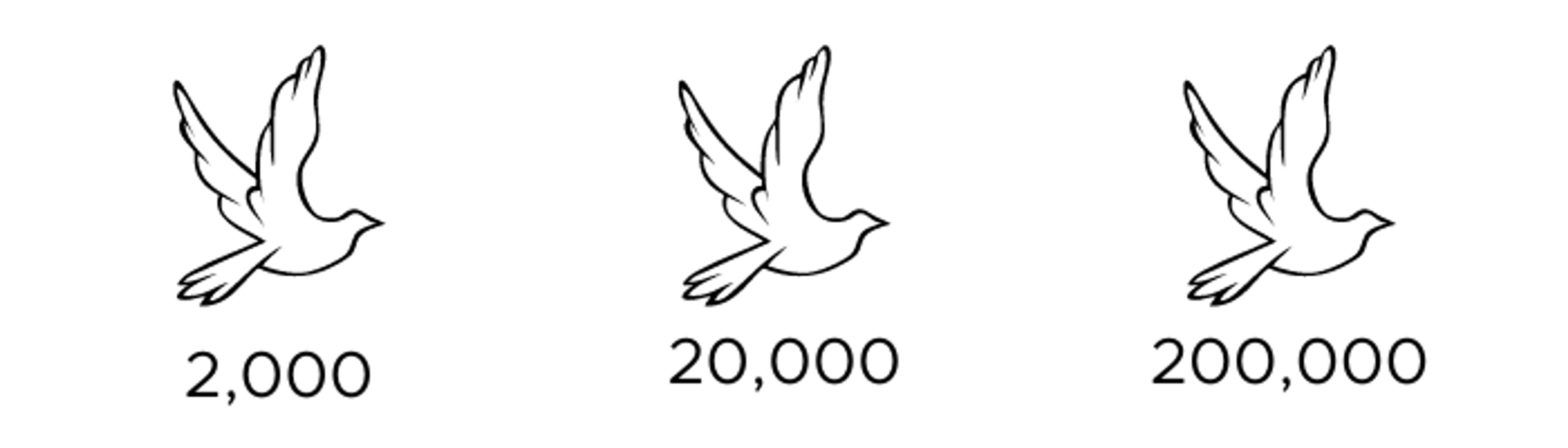

In the aftermath of the Exxon Valdez oil spill in the 1980s, an experiment was conducted that showed a key cognitive bias known as “scope neglect”. People were surveyed about their willingness to pay for nets that would save birds from drowning in oil ponds. Different groups were asked their willingness to pay to save 2,000, 20,000 or 200,000 birds.

You’d think that saving 200,000 birds would be worth much more than saving 2,000 birds. But in fact, on average people said they’d pay $80 to save 2,000 birds, $78 to save 20,000, and $88 to save 200,000. As Kahneman explains, “What the participants reacted to, in all three groups, was a prototype—the awful image of a helpless bird drowning, its feathers soaked in thick oil. The almost complete neglect of quantity in such emotional contexts has been confirmed many times”.

As this experiment demonstrates, we’re sometimes not very good at thinking about sums. We tend to only care about what the experience of an average person (or bird) experiencing a problem is, and ignore how many people (or birds) are actually affected.

This can be a real problem for philanthropic giving: it means we are much more responsive to highly emotive charitable appeals regardless of their potential scale, even if our money might do more good targeting less visceral problems that affect many more people. To get around this, many people assess giving opportunities by looking at their scale, tractability and neglectedness. Doing this helps us ensure that we’re giving our money to the most impactful causes.

2. We give too much weight to problems we know the most about.

One of the biases Kahneman talks about the most is the "availability bias". This is the idea that when we're trying to assess how frequent something is, we tend to make that judgment based just on how easily examples of it come to mind. Because the amount we hear about something is often based on its novelty and excitement — as well as who we know and what we pay attention to (rather than how often the thing actually occurs) — this can lead to misconceptions in how prevalent that thing really is.

For instance, in an experiment where participants were asked whether more people died from tornadoes or asthma, more people picked tornadoes. In fact, asthma causes 20 times more deaths. But because asthma deaths aren't dramatic, they don't get much media coverage — unlike tornadoes, murders and freak accidents — so to most people, asthma seems like a less frequent killer.

The problem goes beyond the media, though. "Personal experiences, pictures, and vivid examples are more available than incidents that happened to others, or mere words, or statistics," Kahneman writes. In the case of philanthropy, that means we might prioritise causes we're personally affected by in the Western world, and neglect problems that we are less aware of, like malaria and vitamin deficiencies.

Once again, being aware of the bias — while not always a perfect solution — can help us become more effective givers. If you remind yourself to pay attention to statistics rather than anecdotes, you might find yourself making better decisions. More importantly, you should remind yourself that there are people (or animals) behind those statistics. If you want to help more people, it often pays to think outside the box, beyond what is happening close to you or what is getting the most attention in the news. (Our list of most effective charities is a good place to start!)

3. We're not good at judging things on their own.

When two things are presented side-by-side, we're good at spotting the differences between them. But when we're asked to evaluate something by itself, we often struggle to call to mind alternatives to compare it to — and this can result in some strange judgments about value. Kahneman highlights an experiment done by Christopher Hsee to explain this.

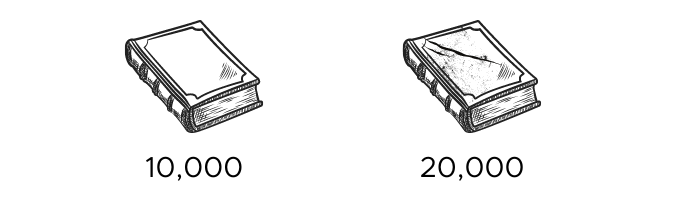

People were asked how much they valued two different dictionaries:

Dictionary A was published in 1993, had 10,000 entries, and was in "like new" condition.

Dictionary B was published in 1993, had 20,000 entries, and its condition was "cover torn, otherwise like new".

.png?w=3840&q=75&fit=clip&auto=format)

When shown the dictionary descriptions one by one, they valued A more highly — B's value was presumably diminished by the torn cover. But when shown the two dictionary descriptions at once (known as a "joint evaluation"), people valued B more highly (because it has many more entries than A).

This is a common problem: when we’re asked to evaluate something by itself, we sometimes form quick judgments about what we think is the “right” amount for some value. But when we’re given two options and asked to compare them, we put in more effort — and come to more logical conclusions.

This is a problem for philanthropy because we often consider donating in a single evaluation setting — we're making a decision whether or not to donate to Charity X, rather than thinking about whether we should donate to Charity X or Charity Y. This reliance on single evaluations might lead to bad decisions about where to donate.

Given that money is finite, and we only have so much to give, each time we’re donating we are implicitly not donating to all the other options out there. So to make sure that we’re giving effectively, we should try to do joint evaluations whenever possible, reminding ourselves of the many alternative philanthropic opportunities that exist. Organisations like GiveWell have developed sophisticated methods for doing this, which allow them to compare effectiveness across causes (e.g. comparing an increase in wages to a decrease in disease prevalence).

4. All of this is really hard!

While the suggestions we've looked at might be handy, they're not foolproof. Kahneman has spent decades studying various cognitive biases, and is more aware of them than most people. And yet even he says "my intuitive thinking is just as prone to overconfidence, extreme predictions, and the planning fallacy as it was before I made a study of these issues." Overcoming the biases turns out to be really difficult.

But don't despair. When it comes to philanthropic giving, there's one easy solution: outsource your decision making to the experts. Some organisations, like GiveWell, Animal Charity Evaluators, or Founders Pledge, might be less bias-prone because they can spend more time evaluating charities, oftentimes in far more detail than a single person could reasonably do. They can dedicate time to do thorough research, which they use to develop models like cost-effectiveness analyses.

What's more, Kahneman says that "organisations are better than individuals when it comes to avoiding errors, because they naturally think more slowly and have the power to impose orderly procedures". If you want to make sure your money does as much good as possible, your intuitions may get in the way. That’s normal. But letting a dedicated and well-staffed organisation decide how to give might mean your donations are going to go even further than if you did all the research yourself.

We’ve got loads of options listed here: to start with, you could take a look at GiveWell’s Maximum Impact Fund, or Effective Altruism Funds.