This post is the first part of an exploration of 'Why sometimes less is more in maternal health'.

The Checklist story - a minimalist's approach

We, the human race, are doing a pretty good job at understanding ourselves - how our bodies work and how they fail. Currently, there are about 14,000 different healthcare diagnoses known to apply to us. Consequently, doctors are armed with 6,000 drugs and 4,000 medical and surgical procedures, which they use in multiple combinations. So medical errors come as no surprise... Medical practice has become incredibly complex and it really takes a village of multi-disciplinary specialists, who each bring a piece of the puzzle, to deliver medical solutions. And as if this wasn't difficult enough, the changing demographic and socio-economic landscape means that there are more of us to treat and we all expect miracles.

Fortunately, human ingenuity might have found just the right solution - the checklist (I am sorry to disappoint any artificial intelligence proponents). A cost-effective tool for streamlining the implementation of evidence-based medical practice, the checklist has gained popularity over the last 15 years. The underlying logic is astonishingly simple: minor missteps in clinical practice can accumulate to BIG problems, meaning higher mortality and morbidity rates, as well as higher costs, which a checklist can help avoid by guiding evidence-based decisions.

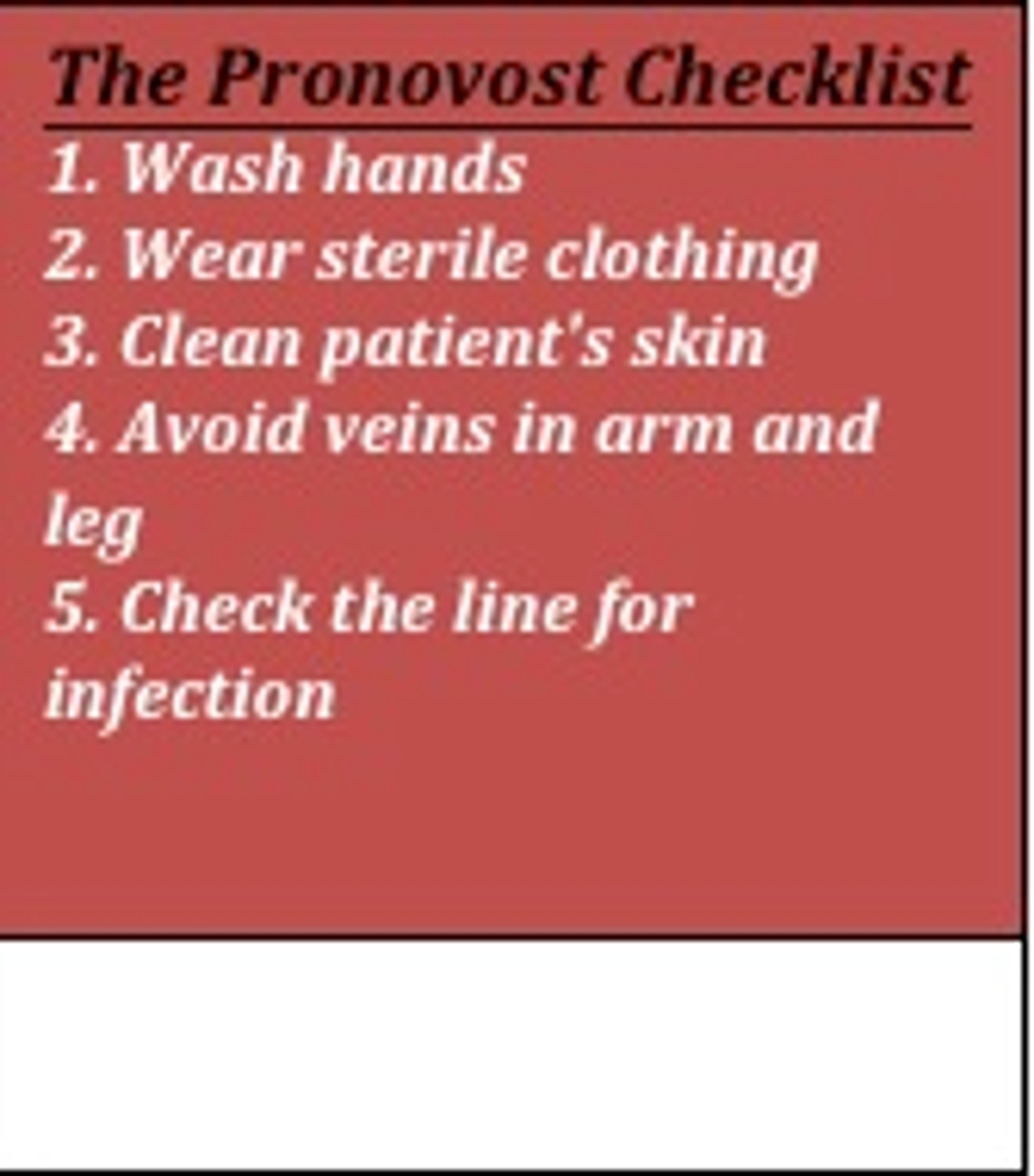

For example, to address one typical such scenario, intravascular catheter-related infection, Dr. Peter Pronovost developed and implemented a simple checklist - the concept was then famously corroborated by Atul Gawane in his article 'The Checklist' [1].

The insertion of a line should be conducted in accordance with five steps (Figure 1) that reduce the chance of developing infection – at least one of those is commonly missed in hospital settings amounting to 80,000 line infections per year in the US [2]. Line infection prolongs the stay of patients in intensive care by at least a week, increasing costs; moreover, between 5% and 28% of line infections lead to death [2]. The implementation of the Pronovost checklist has demonstrated a swift decrease in infection rates (from 11% to 0% in the pilot study in ten days), substantial cost reduction, accompanied by (surprisingly) high staff compliance and a reported sense of empowerment [1].

Of course, the challenges in developing countries differ: even more people to treat, less resources, less highly trained professionals and less fancy medical gadgets. Nevertheless, the need for cost-effective, evidence-based interventions is overwhelming and standardising best practice might empower basically trained healthcare workers to deliver efficient medical solutions.

A Checklist to help combat maternal and neonatal mortality?

The absurdity of maternal mortality is that it takes the lives of 800 women every day and yet there are affordable interventions that can prevent most of these deaths [3,4,5]. A key strategy in tackling existing issues is moving the delivery room from the home to the hospital. Great progress has been achieved in this area, only to highlight that simply hospitalising births is not enough. What's missing is trained clinical staff and reliable medical facilities at these hospitals - the provision of good quality facility-based care remains a global challenge [6-10]. But this is where the checklist could make a difference! Why is it appropriate? Here are three great reasons [11,12]:

- Concentrated action: the majority of deaths occur within 24 hours after birth

- Knowledge is power: the main causes of maternal and perinatal mortality are well documented and international guidelines for best practice exist

- Cost-effective and reproducible: proven interventions are affordable and consist of a multistage sequence of simple interventions.

In 2008, the World Health Organisation (WHO) developed the Safe Childbirth Checklist, a 29-item checklist designed to improve maternal care in a simple, affordable and scalable way [13], originally in ten countries across Africa and Asia. The checklist contains reminders of essential steps for safe childbirth and targets causes of maternal death (haemorrhage, infection, obstructed labour and hypertensive disorders) as well as inadequate neonatal care during and after birth in resource-limited settings [14].

Does it work? The pilot study, in Karnataka, India, demonstrated great compliance - 95% of the health workers adopted the use of the checklist. Furthermore, it was effective - the delivery of essential practices increased from 10 to 25 out of 29 practices. Specific areas of improvement included: appropriate hand hygiene, adequate management of maternal infection and preeclampsia (a cardiovascular disease rooted in pregnancy), maternal blood loss assessment, cutting of the cord with a sterile blade, appropriate administration of oxytocin (medication used to induce labour and reduce bleeding), appropriate newborn thermal and resuscitation management.

Why does it work? The Safe Childbirth Checklist can affect clinical outcome in three main ways: reinforce a set of essential practices to be adhered to during birth, remind health workers of the crucial timing of practices, and identify gaps in existing clinical practice, allowing for improvement.

Is it that simple - the realist's approach

Observers of the pilot study described tangible behavioural changes – e.g. the staff created a postpartum bay for observation of mothers and babies after birth, using an unused space; medical supplies were moved from remote storage into local stacks to better support labour ward workers. However, are these outcomes truly sustainable and scalable? The pilot studies were conducted in first-level referral centres in India with motivated local teams; plus behavioural changes could be driven by the awareness of being observed.

The jury is still out: a multi-centred randomized control trial in more than 100 hospitals has been set up to further evaluate the effectiveness and sustainability of the Safe Childbirth Checklist, with data collection conducted by Harvard School of Public Health between 2013 and 2016 [15]. And we are still to see a detailed quantitative analysis of its cost-effectiveness.

To play devil's advocate, the checklist excitement has been critically named a "Hitchcockian McGuffin", a false objectification of the problem that distracts from the true challenges of delivering safe care [16]. Checklists on their own could be equally unsafe if they are used to install a false sense of security, cloud judgement and consequently plant negligence - the very problem they were designed to tackle. Therefore, any checklist implementation programme should be designed around establishing a higher standard of baseline performance; it should empower clinical workers to improve their practice, minimise avoidable error but be careful not to drive complacency.

Watch out for the maternal checklist!

References

- Gawande, A. The Checklist, The New Yorker, Annals of Medicine, 2010

- Pronovost, P., Needham, D., Berenholtz, S. et al. An Intervention to Decrease Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med, 2006, 355(26), pp. 2725-2732

- Hogan, M. C., Foreman, K. J., Naghavi, M., et al. Maternal mortality for 181 countries, 1980-2008: a systematic analysis of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 5 2010

- Rajaratnam, J. K., Marcus, J. R., Flaxman, A. D., et al. Neonatal, postneonatal, childhood, and under-5 mortality for 187 countries, 1970-2010: a systematic analysis of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 4 2010

- Cousens, S., Blencowe, H., Stanton, C., et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2009 with trends since 1995: A systematic analysis 2011

- Ekirapa-Kiracho, E., Waiswa, P., Rahman, M. H., et al. Increasing access to institutional deliveries using demand and supply side incentives: Early results from a quasi-experimental study 2011

- Harvey, S. A., Blandón, Y. C. W., McCaw-Binns, A., et al. Are skilled birth attendants really skilled? A measurement method, some disturbing results and a potential way forward 2007

- Koblinsky, M., Matthews, Z., Hussein, J., et al. Going to scale with professional skilled care 2006

- Friberg, I. K., Kinney, M. V., Lawn, J. E., et al. Sub-Saharan Africa's mothers, newborns, and children: How many lives could be saved with targeted health interventions? 2010

- Van Den Broek, N. R., Graham, W. J. Quality of care for maternal and newborn health: The neglected agenda 2009

- Tamburlini, G., Yadgarova, K., Kamilov, A. and Bacci, A. Improving the Quality of Maternal and Neonatal Care: The Role of Standard Based Participatory Assessments 2013

- WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990-2008 2010

- Weiser, T. G., Haynes, A. B., Lashoher, A., et al. Perspectives in quality: Designing the WHO surgical safety checklist 2010

- Spector, J. M., Agrawal, P., Kodkany, B., et al. Improving quality of care for maternal and newborn health: Prospective pilot study of the who safe childbirth checklist program 2012

- Safe Childbirth Checklist Programme: an overview, World Health Organization, WHO/HIS/PSP/2013

- Bosk, C.L., Dixon-Woods, M., Goeshel, C.A. and Pronovost, P.J., 2009. Reality check for checklists. Lancet, 374(9688), pp. 444-445