What is microfinance?

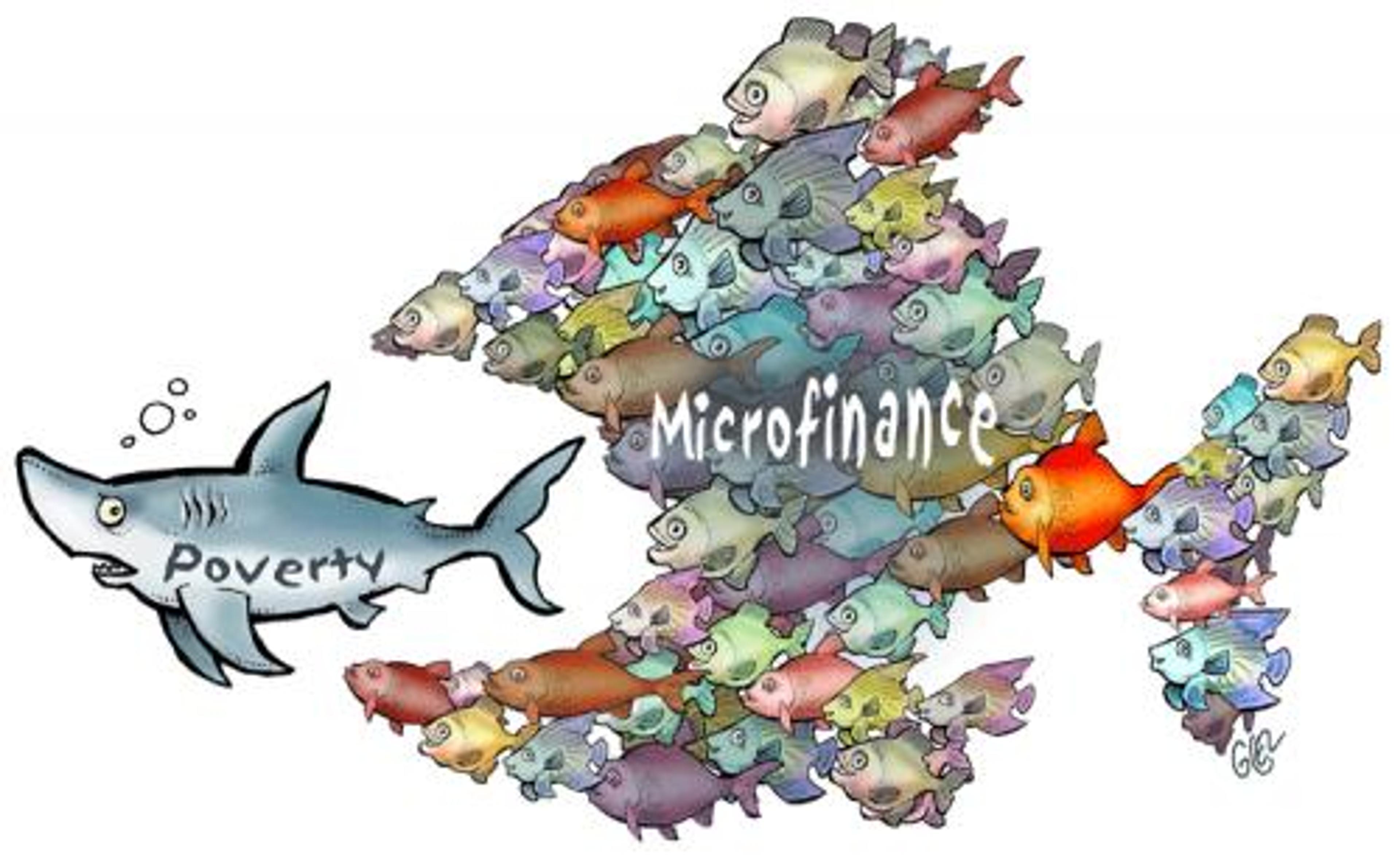

Microfinance is the provision of financial services - loans, savings, and insurance - to those living in poverty. Like those in the developed world, the poor benefit from access to financial services through the ability to fund short and long term consumption needs, cope with unexpected shocks to income and expenses, and invest in business or household items (Matin et al 1999). However, the poor have limited access to more formal financial services, and have thus traditionally relied on a range of institutions, which often charge high premiums or interest rates (Matin et al 1999, Steel et al 1997). Microfinance institutions hope to provide access to those services to a wider range of people living in poverty, in the hope that they will benefit from them. The majority of microfinance institutions, charities, and research projects focus on microcredit - the provision of small collateral-free loans to those who cannot usually get access to credit. We shall do the same here, as the profile and scale of microcredit mean it is the most likely recipient of donations within the microfinance category, and there is more evidence for which we are able to judge its effectiveness.

What are the purported benefits?

There are three main benefits to microcredit which have been most commonly mentioned. Firstly, small landholders and businessmen can use credit to make investments in their farms/businesses to create a return greater than the cost of the loan, creating a cycle of improvement and growth which brings them out of poverty. These are the case studies most typically cited by microfinance charities, and have an intuitive appeal and logic, as well as fitting well with the 'poverty trap' model espoused by Jeffrey Sachs. Secondly, that the provision of credit can enhance the freedom of those in poverty, by giving them options and choices which were otherwise unavailable to them. Thirdly, that microcredit may empower and enhance the status of women, and improve the allocation of household resources towards women and children.

What does the evidence say?

Although there have been studies which have shown positive effects of microcredit on labour supply, school enrolment, expenditure per capita and non-land assets (Pitt & Khandler 1998, USAID studies in Peru, India, Zimbabwe), others have failed to replicate the results and similar studies have received significantly less favourable results and criticised the methodology and data involved (Duvendack et al 2011). Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), often seen as the gold standard for assessing the impact of interventions (although not without issues) have previously been thin on the ground in the area of microcredit, but they have increased in number over the last year, and the majority of recent studies have shown that as a tool to escape poverty - the most commonly cited benefit of microcredit - it does not perform well. Studies from the past year have found no statistically significant evidence of an increase in socio-economic indicators such as income, consumption, health, and education (despite businesses expanding) after RCTS of microcredit in a variety of countries: Morocco (Crépon et al. 2013), Ethiopia (Tarozzi et al. 2013) Bosnia-Herzegovina (Augsburg et al. 2014), Mexico (Angelucci et al. 2013) and India (Banerjee et al. 2013). This is a conclusion reached by the majority of individual methodologically sound studies, as well as major systematic reviews of the available evidence (van Rooyen et al., Duvendack et al 2011, Banerjee 2013).

Further, while some may benefit from microcredit, there is significant evidence that for some it has potential for harm (van Rooyen et al 2012, Roodman 2012), in a similar manner perhaps to payday loans in the developing world, a comparison which GiveWell have drawn. While some recent studies do not find evidence of harm on income (Angelucci et al. 2013), even they do not find significant positive impact. Even if for many microcredit was a tool to escape poverty (which is far from clear) donors would rightly be concerned about funding an intervention which may actually cause harm to some. Further, some studies have found a decline in school attendance for those aged 16-19 in families who have had access to microcredit as family businesses expand and draw in labour supply from young adults; the long-term consequences of which are uncertain (Augsburg et al. 2014).

The evidence is more supportive of the ability of microcredit to promote the freedom of those in poverty, but it depends on the situation, and again, credit still has the ability to entrap some people through bad luck or bad judgement (Roodman 2012); moreover, in some areas there is evidence of overlending, with some either borrowing too much or borrowing from multiple borrowers (Planet Rating March 2013). A positive effect of microcredit which is related to freedom is that there is fairly strong evidence that microcredit leads to a decline in consumption on 'temptation goods' such as alcohol and tobacco (Banerjee 2013, Banerjee et al. 2013, Augsburg et al. 2014) for reasons that are unclear.

The effect of microcredit on female empowerment had been contested, with some studies finding positive, but non-uniform effects, and other systematic reviews finding they can neither support nor deny the notion that microcredit is pro-women (Duvendack et al 2011). However, the most recent RCTs from the past year have found no evidence of an increase in female empowerment (Augsburg et al. 2014, Tarozzi et al. 2013, Banerjee et al. 2013, Crepon et al. 2013), although we should note the difficulty of measuring such impacts (van Rooyen et al. 2012)

Other issues

For the above reasons, we cannot recommend microcredit as a good choice for charitable giving. (Given the lack of any conclusive evidence of reliably positive impact, and evidence of some being harmed by microcredit, it is neither worthwhile nor possible to calculate a cost-effectiveness measure of microcredit in order to compare to other interventions). However, there are also other issues which cause us to recommend against microfinance as an avenue for charitable giving at this moment.

Firstly, there is a possibility that better research in the coming years could perhaps reveal which microfinance interventions are the most effective, and create opportunities for giving to microfinance which do have strong, measurable impacts. Indeed, GiveWell recommends the Small Enterprise Foundation as a standout microfinance institution, against a backdrop of strong misgivings over microfinance's effects, suggesting that charities with a commitment to self-evaluation may in the future produce significant, measurable, and repeatable impacts. RCTs from the past year have shifted the balance of debate decisively towards the conclusion that current microfinance initiatives have at best limited effects in experimental studies, and perhaps the next generation of studies will diagnose the reasons for this and design more effective forms of microcredit. Relatedly, there may develop greater opportunities within microfinance in areas other than microcredit, such as microsavings, which has shown promise (Duvendack et al 2011, van Rooyen et al 2012)

Secondly, "microfinance activities and finance have absorbed a significant proportion of development resources, both in terms of finances and people" (Duvendack et al 2011), and have also seen the entrance of many commercial operations. This raises questions over whether there is room for more funding, and even in some areas whether additional funding would result in overlending and actually cause harm, as may be the case in Peru.

Thirdly, GiveDirectly performs a similar role - the only difference being that the 'loan' is not repaid - and has strong evidence of significant impacts.

Conclusion

Despite a strong narrative and intuitive appeal, we cannot recommend microfinance institutions as a recipient of effective-giving. The available evidence finds no statistically significant improvement on poverty-related outcomes or female empowerment (and indeed it may negatively affect some recipients), while the effect on most freedom-related outcomes is varied and inconclusive. Further, microfinance has received significant attention and resources while other less heralded interventions which have shown significant effects have received far less funding. Recent RCTs strongly support the conclusion that the impact of microcredit on poverty is limited at best, and more high-quality research from academia and microfinance institutions is necessary to reveal the effects and pathways more clearly, as well as to inform best practice.

Bibliography

Angelucci, M., D. Karlan, and J. Zinman (2013). Win some lose some? Evidence from a randomized microcredit program placement experiment by Compartamos Banco. Working Paper.

Attanasio, O., B. Augsburg, R. D. Haas, E. Fitzsimons, and H. Harmgart (2013). Group lending or individual lending? Evidence from a randomised field experiment in Mongolia. EBRD Working Paper No. 136.

Augsburg, B., De Haas, R., Harmgart, H., Mehgir, C., (2014). Microfinance at the margin: experimental evidence from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Working Paper.

Banerjee, A. (2013). Microcredit under the microscope: What have we learned in the past two decades, and what do we need to know? Annual Reviews of Economics 5, 487{519.

Banerjee, A., E. Duflo, R. Glennerster, and C. Kinnan (2013). The miracle of microfinance? Evidence from a randomized evaluation. MIT Department of Economics.

Crépon, B., F. Devoto, E. Duflo, and W. Pariente (2013). Estimating the impact of microcredit on those who take it up: Evidence from a randomized experiment in Morocco. Working Paper.

Duvendack, M., Palmer0Jones, R., Copestake, J., Hooper L., Loke Y. and Rao, N., (2011), 'What is the evidence of the impact of microfinance on the well-being of poor people?', August 2011, London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London

Matin, I., Hulme, D., Rutherford., S (1999). Financial services for the poor and poorest: deepening understanding to improve provision. Finance and development research programme working paper series no. 9. Manchester: IDPM, University of Manchester Pitt, M., Khandker, S., (1998) The impact of group-based credit programmes on poor households in Bangladesh: does the gender of participants matter? Journal of Political Economy, 106 (5): 958-996.

Roodman, D., (2012). Due Diligence: An impertinent inquiry into microfinance. Centre for Global Development

Steel, W. F., Aryeetey, E., Hettige, H. and Nissanke M. (1997), 'Informal Financial Markets Under Liberalization in Four African Counties', World Development, vol. 25, no. 5, pp. 817-830, Elsevier Science Ltd.

Stewart, R., van Rooyen, C., Korth, M., Chereni, A., Rebelo Da Silva, N., de Wet, T., (2012) Do micro credit, microsavings and microleasing serves as effective financial inclusion interventions enabling poor people, and especially women, to engage in meaningful economic opportunities in low and middle income countries. A systematic review of the evidence. London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London

Tarozzi, A., Desai, J., Johnson, K., (2013), On the impact of microcredit: evidence from a randomized intervention in rurar Ethiopia. Working Paper