An update on the effectiveness of the micronutrient fortification programmes by Project Healthy Children (PHC) (Working Paper)

Hauke Hillebrandt, Ph.D., Mark Engelbert, Ph.D.

Email: hauke.hillebrandt@givingwhatwecan.org

Summary

Project Healthy Children (PHC) is a charity that we began investigating in recent years, and it has been one of our promising charities for nearly 2 years.

We have reviewed Project Healthy Children in the past and also written an introduction on micronutrient fortification . Our colleagues at Givewell have not officially reviewed PHC, but provide a great overview in form of a conversation note with PHC’s Chief operating officer, Laura Rowe. Givewell has also published extensive intervention reviews on Micronutrient fortification as implemented by Project Healthy Children ( Salt iodization, Vitamin A fortification, Zinc fortification ). Finally, they have also written reports on organisations similar to PHC, such as GAIN and IGN . These programmes are generally considered to be very effective and some of the effectiveness analyses are generalizable to PHC.

In this paper, we give you an update about their efforts that we feel complement Givewell’s intervention reports and our previous report. You can find more general information about PHC on our website . In our opinion, PHC continues to be a very promising charity with potentially a very high cost-effectiveness.

Recent Scientific findings that relate to PHC’s effectiveness

Differences between micronutrient supplementation and fortification

To begin, note that there is a difference between micronutrient supplementation and micronutrient fortification. Micronutrient supplementation is here defined as taking capsules or foodstuffs (such as biscuits) that are specifically made to increase micronutrient status of the person eating it, whereas fortification means that commonly eaten staple foods are enriched with micronutrients. Although the aim of this report is to examine the effectiveness of micronutrient fortification, the close relation between supplementation and fortification means that sometimes results from micronutrient supplementation can provide insight into the effectiveness of fortification. Supplementation of all foods is often not as viable or as cost-effective as fortification. Also a recent study suggests that in pregnant adolescents, prenatal supplements cannot fully compensate for preexisting dietary deficiencies [1] ; thus, even if supplementation could be cost-effectively distributed to whole populations, it might still be less effective at improving nutritional outcomes than a continuous diet of enriched food by means of micronutrient fortification. Finally, there is also bio fortification, which is increasing the micronutrient content of plants directly, which will not be discussed here.

General considerations of micronutrient fortification

A recent systematic review of 201 studies on the impact of micronutrient fortification of food and on woman and child health [2] , concludes that fortification is promising, but because of high burdens of diarrhea and intestinal inflammation, widespread malabsorption may decrease its effectiveness. Further, even though fortification is potentially an effective strategy, evidence from the developing world is scarce and future programs should measure the direct impact of fortification on morbidity and mortality.

Epidemiology of malnutrition

While underweight is the number-one contributor to the burden of disease in sub-Saharan Africa [3] , [4] , nutritional deficiencies make up a large part of the overall direct disease and disability burden in developing countries (see Figure 1) . However, nutritional deficiencies are linked to other diseases (see Figure 2), and so over 50% of years lived with disability in children can be traced to these deficiencies [5] , [6] .

Figure 1: Overall “Years Lost due to Disability (YLD)” in developing countries. Nutritional deficiencies are marked in black and make up 7.89% of the total YLDs. Figure adapted with ‘Global Burden of Disease Compare tool’- see http://ihmeuw.org/3a5f . © 2013 University of Washington - Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (Global burden of Disease data 2010, released 3/2013)

Updates from countries in which PHC is currently active

The following updates are quotes from the World Bank’s 2013 ‘Nutrition at a Glance’ country reports of those countries in which PHC is active.

Rwanda [7]

Annually, Rwanda loses nearly US$50 million in GDP to vitamin and mineral deficiencies.

Scaling up core micronutrient interventions would cost US$6 million per year.

52% of children under the age of five are stunted, 16% are underweight, and 5% are wasted. 6% of infants are born with a low birth weight. Rwanda’s progress over the past two decades has not improved to meet MDG 1c (halving 1990 rates of child underweight by 2015) with business as usual.

Rwanda performs worse than countries in its region and income group. Countries with lower per capita incomes, such as Togo and DRC exhibit reduced rates of child stunting.

Rwanda has Higher Rates of Stunting than Lower-Income Peers GNI per capita (US$2008).

Figure 3: Figure shows risk factors for “Disability adjusted life years” in Rwanda. Micronutritional deficiencies, such as Iron, Zinc, and Vitamin A deficiencies, are substantial risk factors. Figure adapted with ‘Global Burden of Disease Compare tool’- see http://ihmeuw.org/3hck . © 2013 University of Washington - Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (Global burden of Disease data 2010, released 3/2013)

Malawi [8]

Annually, Malawi loses over US$600 million in GDP to vitamin and mineral deficiencies. Scaling up core micronutrient interventions would cost less than US$9 million per year.

Malawi has the 5th-highest stunting rate in the world. 53% of children under the age of five are stunted, 15% are underweight, and 4% are wasted. 13% of infants are born with a low birth weight. Malawi’s progress over the past two decades has not improved to meet MDG 1c (halving 1990 rates of child underweight by 2015) with business as usual.

Malawi’s stunting rates are higher than many of its income peers in Africa. While per capita income is very low in Malawi, other countries show that it is possible to reduce stunting with the same or lower GNI.

Figure 4: Figure shows risk factors for “Disability adjusted life years” in Malawi. Micronutritional deficiencies, such as Iron, Zinc, and Vitamin A deficiencies, are substantial risk factors. Figure adapted with ‘Global Burden of Disease Compare tool’- see http://ihmeuw.org/3hck . © 2013 University of Washington - Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (Global burden of Disease data 2010, released 3/2013)

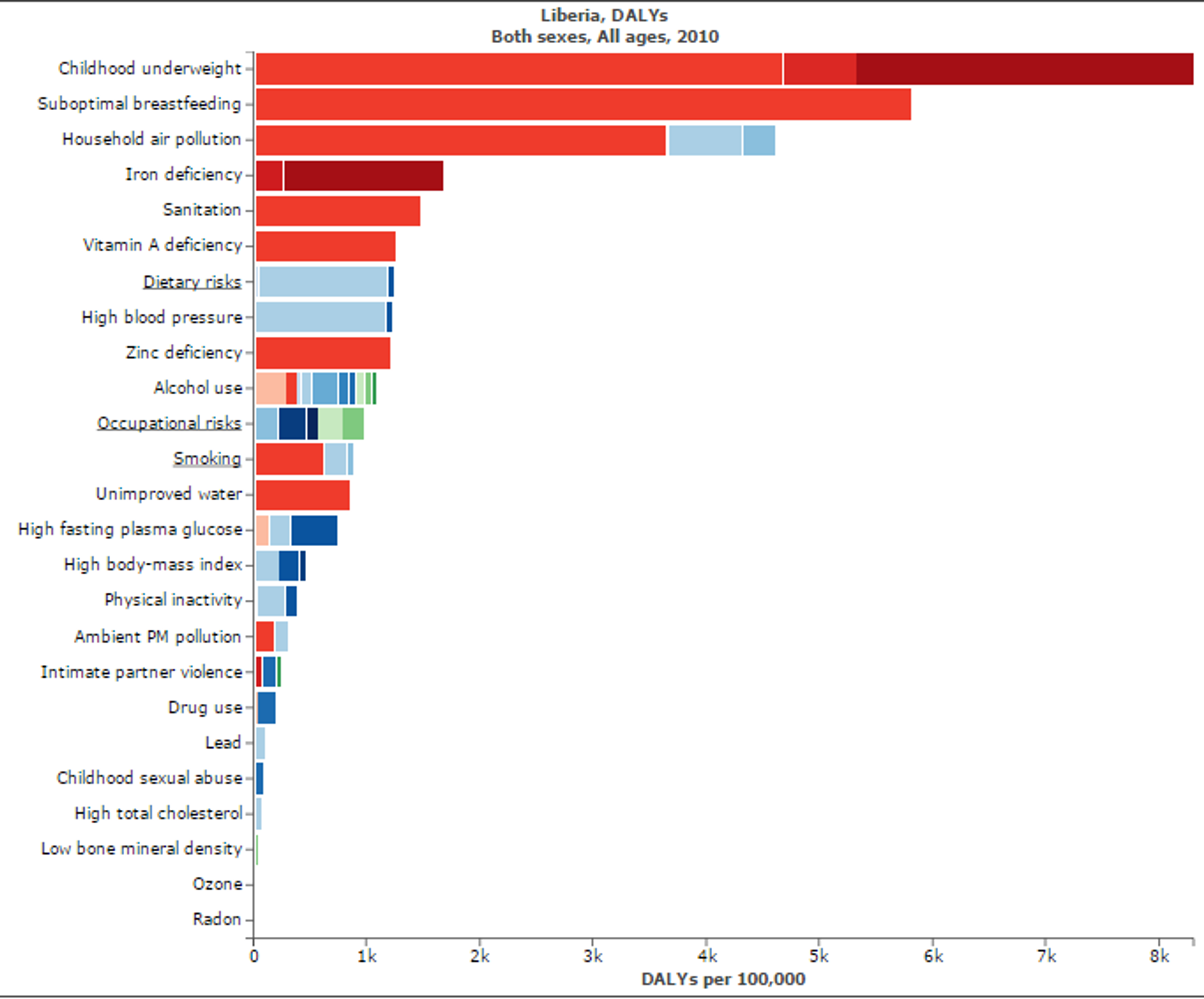

Liberia [9]

Annually, Liberia loses over US$11 million in GDP to vitamin and mineral deficiencies. Scaling up core micronutrient nutrition interventions would cost US$2 million per year

39% of children under the age of five are stunted, 19% of children under the age of five are underweight, and 8% are wasted.

Liberia will not meet MDG 1c (halving 1990 rates of child underweight by 2015) with business as usual. 14% of infants are born with a low birth weight.

Liberia’s stunting rates are higher than many countries in the Africa region with similar per capita income.

Figure 5: Figure shows risk factors for “Disability adjusted life years” in Liberia. Micronutritional deficiencies, such as Iron, Zinc, and Vitamin A deficiencies, are substantial risk factors. Figure adapted with ‘Global Burden of Disease Compare tool’- see http://ihmeuw.org/3hck . © 2013 University of Washington - Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (Global burden of Disease data 2010, released 3/2013)

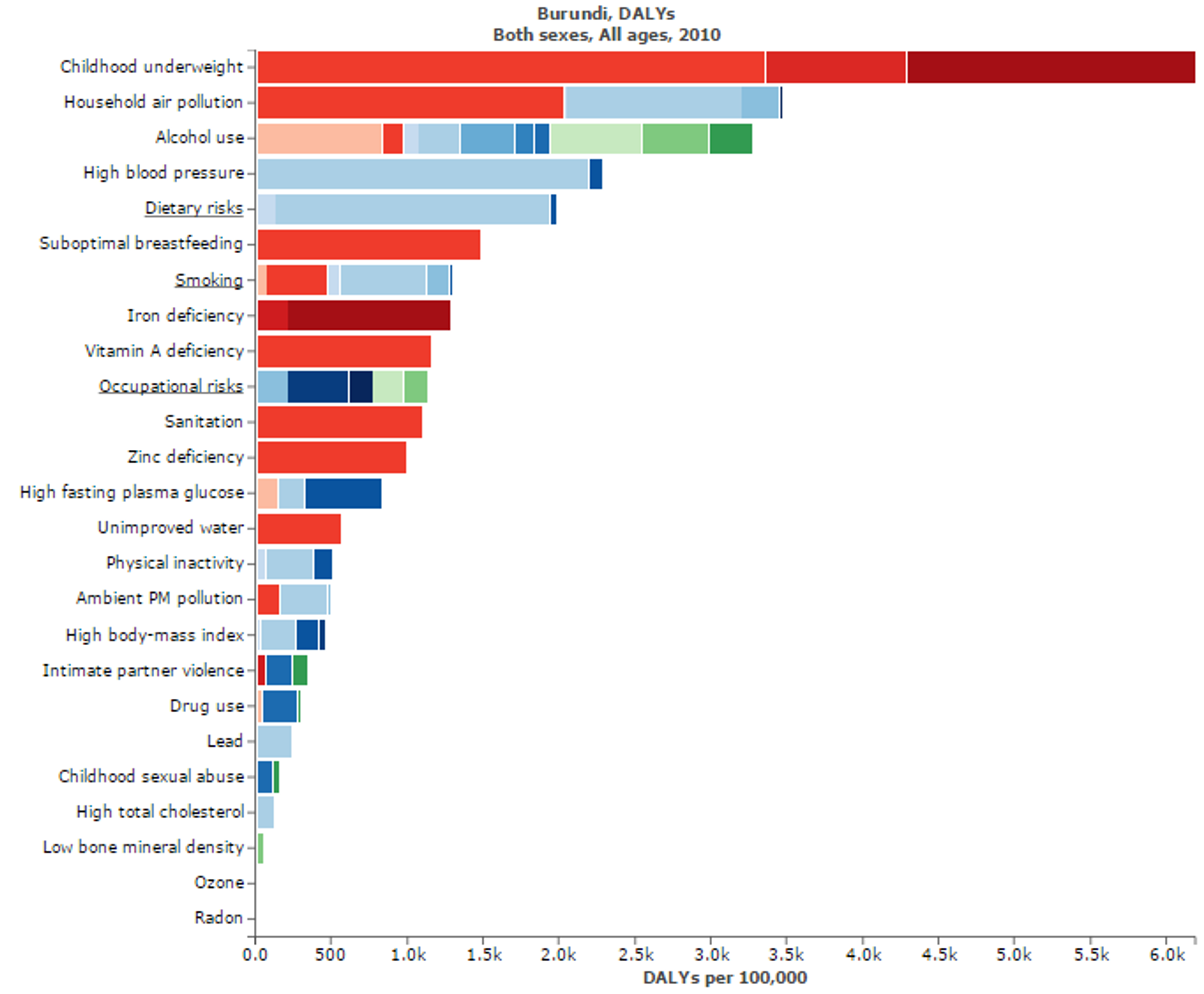

Burundi [10]

Annually, Burundi loses US$30 million to vitamin and mineral deficiencies. Scaling up core micronutrient interventions would cost US$4 million per year.

53% of children under the age of five are stunted, 35% are underweight, and 7% are wasted. 11% of infants are born with a low birth weight...the prevalence of stunting is substantially higher in Burundi compared to other countries in the Africa region with similar per capita incomes. It is possible to achieve better nutrition outcomes despite low income.

Figure 6: Figure shows risk factors for “Disability adjusted life years” in Burundi. Micronutritional deficiencies, such as Iron, Zinc, and Vitamin A deficiencies, are substantial risk factors. Figure adapted with ‘Global Burden of Disease Compare tool’- see http://ihmeuw.org/3hck . © 2013 University of Washington - Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (Global burden of Disease data 2010, released 3/2013)

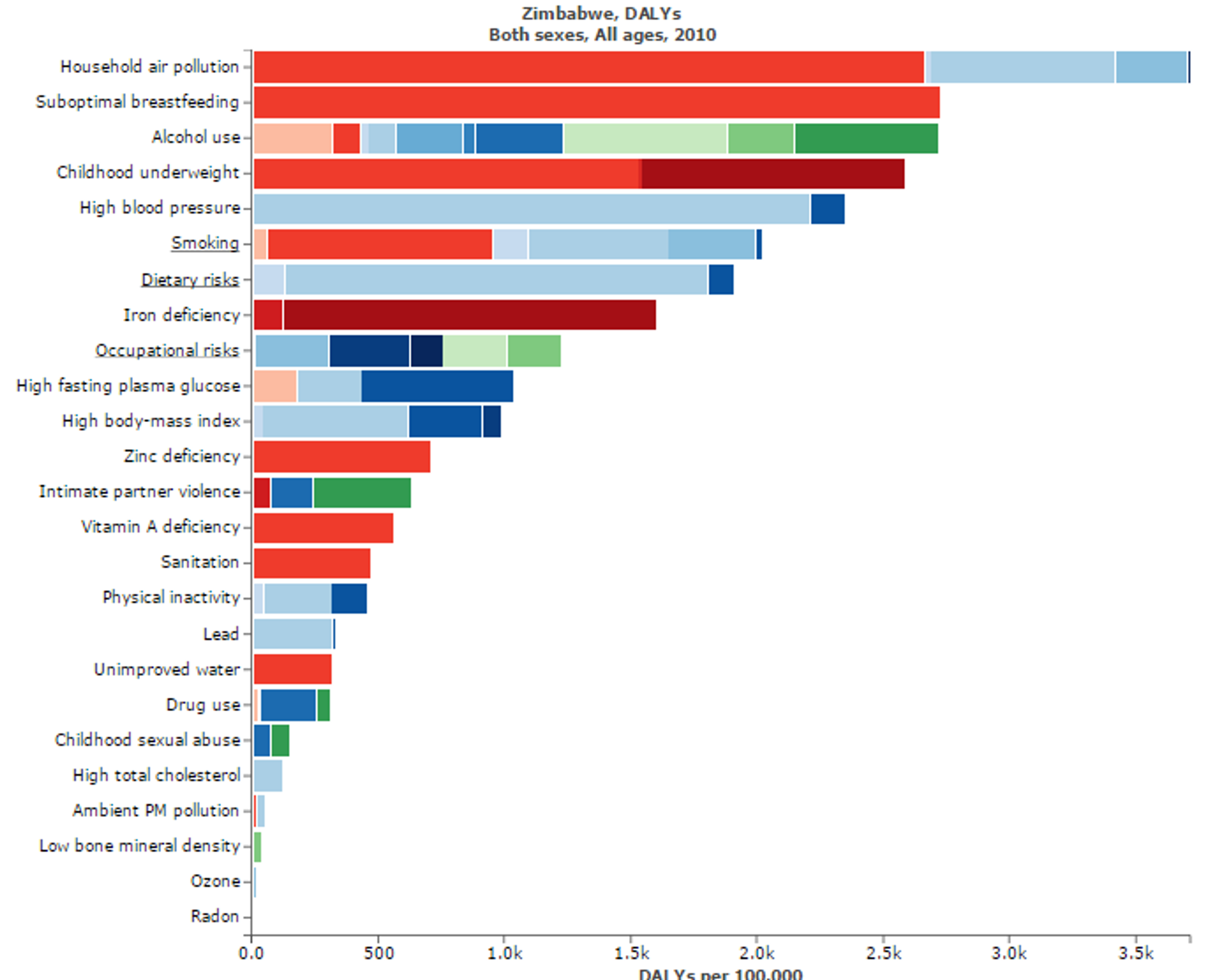

Zimbabwe [11]

Annually, Zimbabwe loses nearly US$24 million in GDP to vitamin and mineral deficiencies. Scaling up core micronutrient interventions would cost less than US$8 million per year.

33% of children under the age of five are stunted, 12% are underweight, and 7% are wasted. 11% of infants are born with a low birth weight. Zimbabwe is currently not on track to meet MDG 1c (halving 1990 rates of child underweight by 2015) with business as usual. When overall rates of child stunting are examined, Zimbabwe performs better than countries in its region and income group. However, within the country, there is likely to be variation across geographies and socio-demographic groups.

Figure 7: Figure shows risk factors for “Disability adjusted life years” in Zimbabwe. Micronutritional deficiencies, such as Iron, Zinc, and Vitamin A deficiencies, are substantial risk factors. Figure adapted with ‘Global Burden of Disease Compare tool’- see http://ihmeuw.org/3hck . © 2013 University of Washington - Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (Global burden of Disease data 2010, released 3/2013)

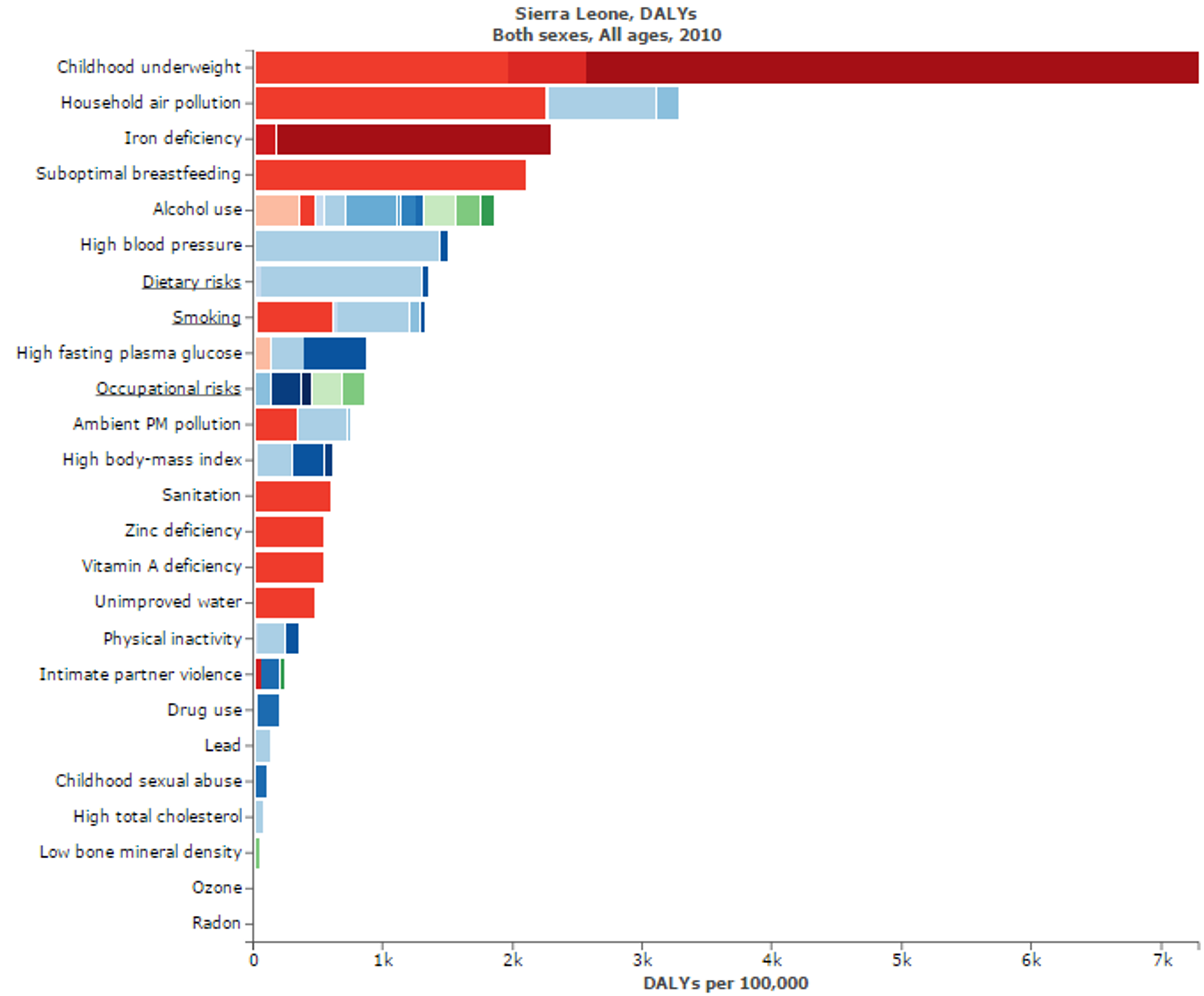

Sierra Leone [12]

Annually, Sierra Leone loses over US$28 million in GDP to vitamin and mineral deficiencies. Scaling up core micronutrient interventions would cost less than US$4 million per year.

36% of children under the age of five are stunted, 21% are underweight, and 10% are wasted. Almost 1 in 4 infants are born with a low birth weight. Sierra Leone will not meet MDG 1c (halving 1990 rates of child underweight by 2015) with business as usual.

Sierra Leone exhibits higher rates of child stunting relative to some other countries with similar per capita income. That Zimbabwe, The Gambia, and Togo have much lower stunting rates demonstrates that it is possible to achieve better nutrition outcomes despite low income.

Figure 8: Figure shows risk factors for “Disability adjusted life years” in Sierra Leone. Micronutritional deficiencies, such as Iron, Zinc, and Vitamin A deficiencies, are substantial risk factors. Figure adapted with ‘Global Burden of Disease Compare tool’- see http://ihmeuw.org/3hck . © 2013 University of Washington - Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (Global burden of Disease data 2010, released 3/2013)

Cost-effectiveness of different micronutrient fortification interventions

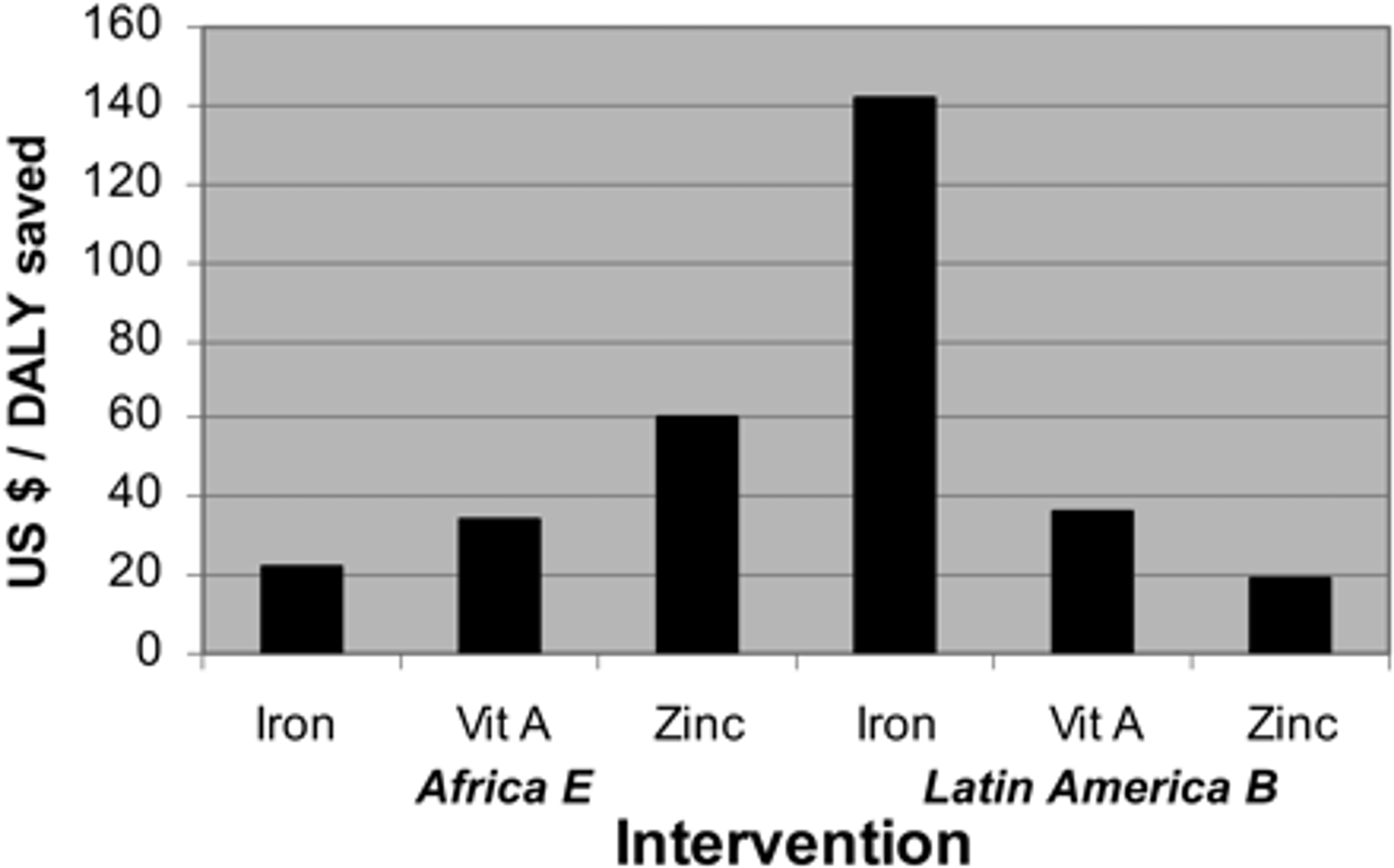

Even though there are some uncertainties with regard to estimating the cost-effectiveness of micronutrient fortification programmes and there is variation in cost-effectiveness across programmes [13] , fortification is generally considered to be a very cost-effective intervention. Early estimates suggested that fortification with iron, vitamin A and zinc were well below $100 per DALY averted (see Figure 9 ).

Figure 9: Comparison of cost effectiveness of fortification in East Africa. Figure adapted from [14]

A 2006 report from the Disease Control Priorities Project suggests that overall cost-effectiveness is US$66 to US$70 per DALY averted for iron fortification programs and US$34 to US$36 per DALY averted for iodine fortification programs [15] .

There is now a vast literature on the cost effectiveness of micronutrient fortification. A recent review article [16] on the economics of nutrition summarizes the evidence of cost-effectiveness for different micronutrient programmes (see Table 2 of this review for a summary of research papers on the topic [17] ). Two studies from this paper provide $ per DALY averted estimates of fortification programmes:

- Folic acid fortification in Chile: costs per neural tube defect case and infant death averted were I$1,200 [18] and I$11,000, respectively; cost per DALY averted was I$89; net cost savings of fortification were I$2.3 million

- Vitamin A fortification of edible oils and sugar in Uganda: Cost per DALY averted is US $82 for sugar fortification and $18 for oil fortification

A 2009 review by John Fiedler and Barbara MacDonald [19] provides cost-per-DALY-averted estimates for micronutrient fortification programmes in many countries. Although these were not programmes implemented by PHC, they were adopted in many of the same countries where PHC operates. Thus, these data provide some indication of likely cost effectiveness levels that can be expected for similar programmes implemented by PHC in these same countries. Tables 1 and 2 are adapted from Fiedler and MacDonald’s review to show only countries in which Project Healthy Children is currently operating. These estimates suggest high cost-effectiveness at around $100 per DALY averted, similar to previous high cost-effectiveness estimates of fortification programmes in other countries (see Table 1 ). Table 2 summarizes key statistics for micronutrient programmes in a number of countries in which PHC operates, along with each programme’s ranking among worldwide programmes in terms of cost effectiveness. For instance, wheat fortification in Malawi was the 16th most cost-effective food fortification programme in the world. Taken together, these data indicate that PHC operates in countries where micronutrient fortification programmes have proved to be cost-effective. It should be noted, however, that this table is from 2009, and it is possible that many of the most cost-effective programmes (i.e., the ‘low hanging fruit’) have in the meantime been executed.

| Country | Cost per DALY averted (USD) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sugar | Vegetable oil | Maize flour | Wheat flour | |||

| (Reduced Program) | (Expanded Program) | (Reduced Program) | (Expanded Program) | |||

| Burundi | — | 106 | — | — | — | — |

| Malawi | 223 | 105 | 183 | 120 | 24.61 | 10.81 |

| Rwanda | 225 | 68 | — | — | — | — |

| Sierra Leone | — | 69 | — | — | — | — |

| Zimbabwe | 33 | 487 | 2232 | 1060 | 42.54 | 31.78 |

TABLE 1: Total incremental 10-year cost and cost per DALY averted arrayed alphabetically by countries in which PHC operates in. Figure adapted from [20] . Full table here [21]

| Rank | Country | Food | Total cost (US$) | Cost per DALY saved (US$) | Cumulative total cost (US$) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | Malawi | wheat | 1,344,446 | 25 | 24,074,848 |

| 21 | Zimbabwe | sugar | 2,218,527 | 33 | 139,567,326 |

| 30 | Zimbabwe | wheat | 1,872,396 | 43 | 252,005,760 |

| 46 | Rwanda | oil | 6,623,699 | 68 | 482,470,004 |

| 47 | Sierra Leone | oil | 10,601,950 | 69 | 493,071,954 |

| 52 | Malawi | oil | 9,738,123 | 105 | 733,345,516 |

| 54 | Burundi | oil | 5,500,917 | 106 | 788,260,013 |

TABLE 2. The ranking of the countries PHC is active in from a table of the 60 countries’ micronutrient interventions arrayed by cost per DALY averted. Table adapted from [22] . Full table here [23]

In sum, even though these cost-effectiveness estimates are subject to limitations (i.e., up-to-date cost-effectiveness estimates of the exact fortification programmes that PHC conducts are unavailable, and cost-effectiveness estimates are sometimes uncertain and difficult to compare), overall we believe that that the available evidence suggests PHC’s cost-effectiveness is roughly similar to the reported estimates—in other words, that PHC’s programmes are highly cost-effective.

Economic effects

Nutritional deficiencies have been shown to have negative economic consequences. Out summary of these effects draws from several recent studies, including the Global Nutrition Report 2014 [24] . Note that micronutrient deficiencies only account for part of the economic losses from nutritional deficiencies—macronutrient deficiencies (i.e., hunger) also contribute to these losses.

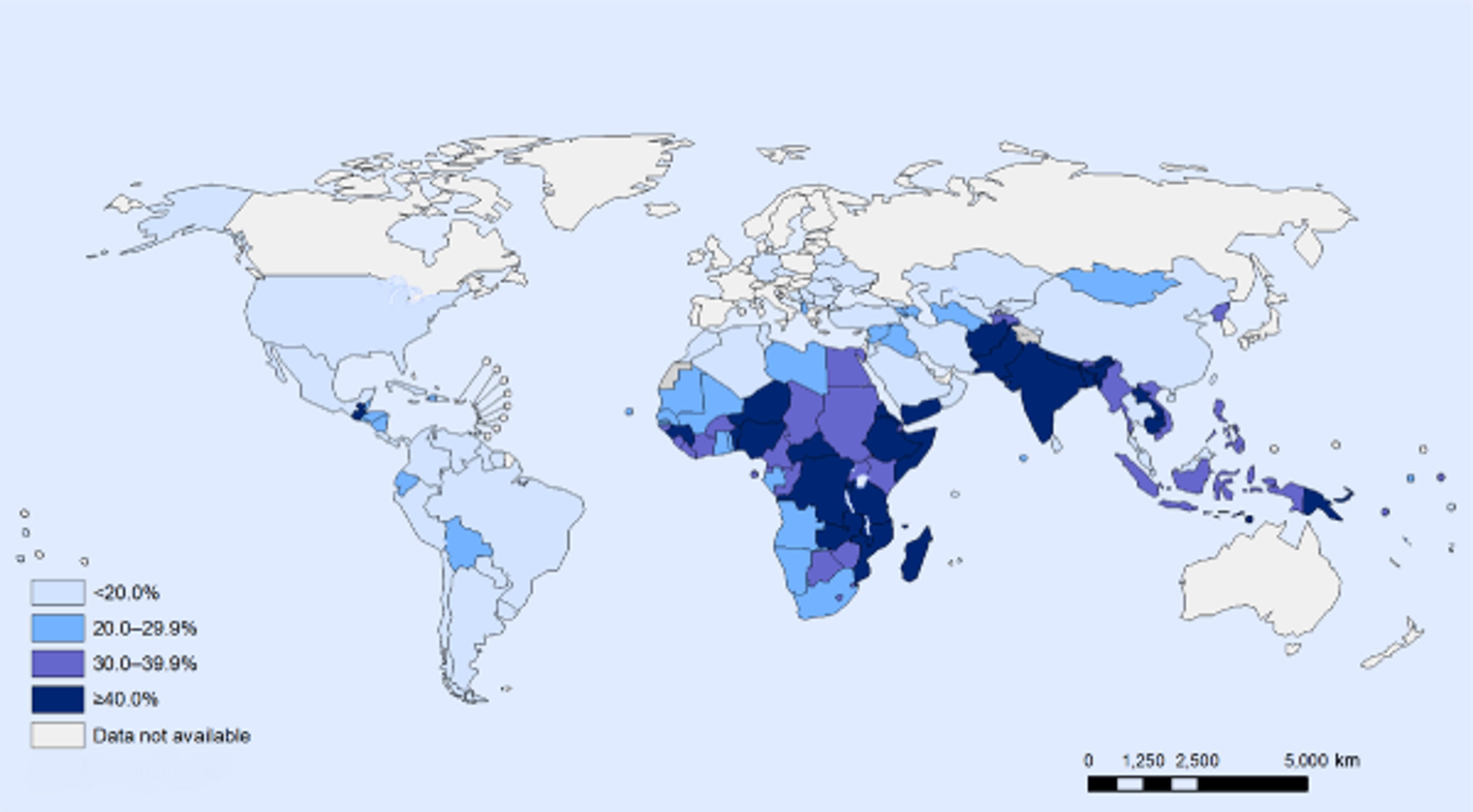

Labour productivity lost

A study from Guatemala suggests that preventing undernutrition in childhood increases productivity in several ways. Specifically, preventing undernutrition increases hourly earnings by 20% and wage rates by 48%. Moreover, children treated for undernutrition are 33% more likely to escape poverty, while treated girls are 10% more likely to own a business as adults [25] , [26] . Stunted growth or stunting, is a reduced growth rate in human development due to nutritional deficiencies, is highly prevalent in developing countries (see Figure 10 ) and a significant contributor to lost productivity. Analyses suggest that growth failure in early life has profound adverse consequences over the life course on human, social, and economic capital [27] . One study in particular showed that one extra centimeter of adult height corresponds to a 4.5% increase in wage rates [28] , [29] . Low birth weight is also associated with increased risk of hypertension and kidney disease in later life; however, micronutrient supplementation during pregnancy reduces the risk of low birth weight and prematurity [30] .

Figure 10: Stunting among children under 5: latest national prevalence estimates. Figure taken from [31]

Macroeconomic Impact

Economic analyses suggest that undernutrition within a country lowers the overall economic productivity of that country. Specifically, undernutrition has been suggested to lower GDP for Egypt by 1.9%; Ethiopia, 16.5%; Swaziland, 3.1%; and Uganda, 5.6% [32] . Asia and Africa lose 11% of GNP every year owing to poor nutrition [33] . One recent study suggests that, in Cambodia, malnutrition costs more than US $400 million annually, corresponding to -2.5% of the country’s GDP. In Pakistan, protein malnutrition, iodine deficiency and iron deficiency collectively accounted for about 3–4% of gross domestic product (GDP) loss annually [34] , [35] . A study of 10 developing countries suggest that iron-deficiency anaemia causes an average loss of 4.5% of GDP [36] , [37] .

A recent World Bank study estimated that investing in nutrition can increase a country’s GDP by at least 3 percent annually [38] . The same study concluded that global benefit-to-cost ratio of micronutrient powders for children is 37 to 1; of deworming it is 6 to 1; of iron fortification of staples it is 8 to 1; and of salt iodization is 30 to 1 [39] .

We have calculated the average benefit-to-cost ratio of fortification programmes in the countries where PHC is active. Using the World Bank’s estimates of the economic on GDP loss annually to vitamin and mineral deficiencies alone [40] , we have calculated [41] that the average benefit-to-cost ratio in these countries is about 23:1. In other words, the cost of scale-up for fortification programmes is 23 times smaller than the economic benefits. Other researchers have found similarly high estimates of cost-effectiveness: a recent paper [42] looked at the value of stunting-reducing nutrition investments, such as micronutrient fortification, in 17 high-burden countries. The benefit-to-cost ratios ranged from 3.6 (Democratic Republic of Congo) to 48 (Indonesia) with a median value of 18 (Bangladesh). Another recent paper [43] , [44] finds similarly impressive benefit-cost ratios for iodizing salt (80), iron supplements for mothers and small children (24), vitamin A supplementation (13), and zinc supplementation for children (3). Thus, these estimates in the literature are broadly comparable to our calculations.

Effects of micronutrients for mental development

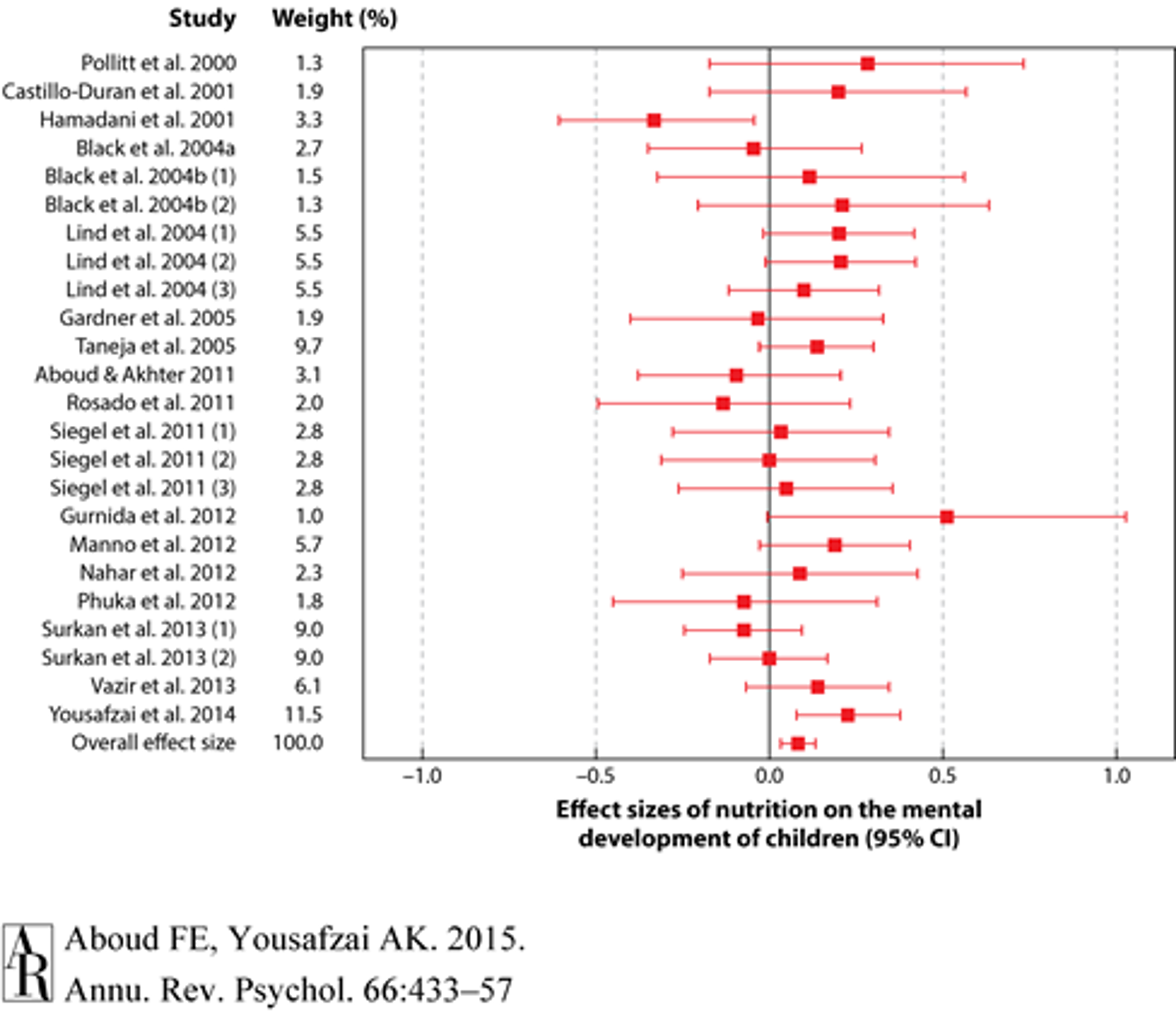

A review and meta-analysis of 21 interventions examined the effects of multiple micronutrients on mental development, and yielded a very small but significant overall effect size of d = 0.09 [45] , [46] (see Figure 11) . However, even small effect sizes can translate to very high cost-effectiveness, so long as the effects are robust and the interventions are very cheap to implement. However, it is very difficult to estimate the exact cost-effectiveness.

Figure 11 [47] Forest plot for effect sizes (standard mean difference represented as a red square and 95% confidence interval represented as red lines) of nutrition on the mental development of children. Overall effect size was 0.086 (95% CI 0.034, 0.137).

Moreover, another recent study showed that across several countries improving linear growth in children under two years of age by 1 standard deviation adds about half a grade-level to school attainment [48] .

Micronutrient supplementation for children with HIV infection

A recent systematic Cochrane review summarized the available evidence on micronutrient supplementation for children with HIV infection [49] . The authors conclude that both Vitamin A and zinc supplementation are safe and carry benefits for children with HIV infection (in particular, zinc appears to have similar benefits in terms of reducing death due to diarrhea in children with HIV as in children without HIV infection. Finally, Cochrane suggests that multiple micronutrient supplements have some clinical benefit in poorly nourished, HIV-infected children.

Recent research on fortification with specific micronutrients

Iodine fortification

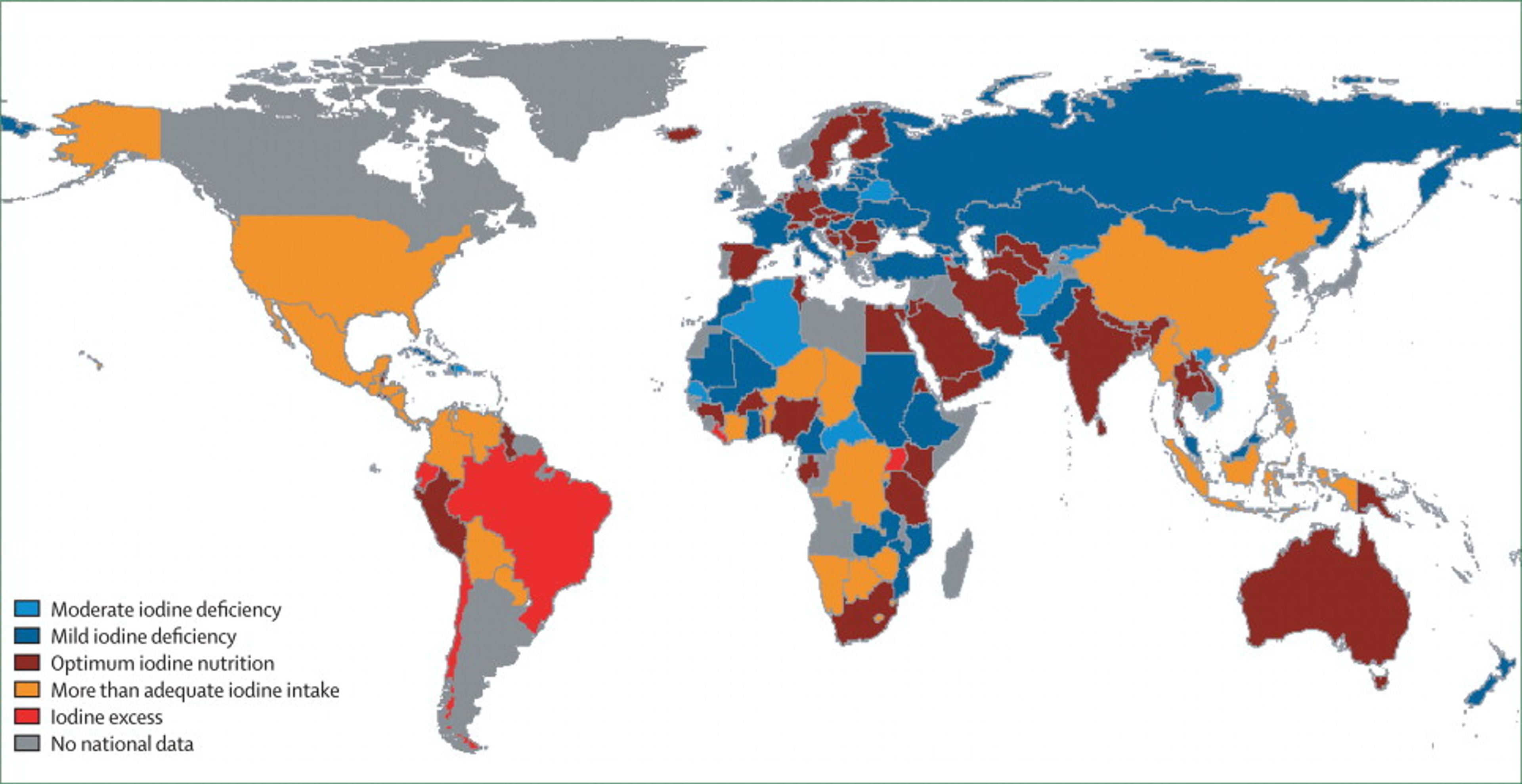

Iodine deficiency disorders are prevalent in many African countries (see Figure 7 ), where they make up a substantial part of the overall disease burden (see Figures 8 and 9 ).

Figure 12: Iodine nutrition based on the median urinary iodine concentration, by country [50]

Figure 13 . Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) (thousands) lost due to iodine deficiency in children younger than 5 years of age, by region [51]

Figure 14: Overall “Years Lost due to Disability (YLD)” in developing countries. Iodine deficiency are marked in black and make up 0.56% of the total YLDs. Figure adapted with ‘Global Burden of Disease Compare tool’- see http://ihmeuw.org/3a5v . © 2013 University of Washington - Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (Global burden of Disease data 2010, released 3/2013)

Benefits and Risks of Iodine

One risk of iodine supplementation is the possibility of iodine excess. Iodine excess has been suggested to cause hyper- and hypothyroidism, goitre and thyroid autoimmunity, effects which can occur even near the upper recommended daily intake of iodine [52] . In some instances, thyroid autoimmunity and hypothyroidism have been observed after the introduction of salt iodization programmes [53] .

However, most researchers agree [54] , [55] , [56] that the available evidence suggests that the benefits of correcting iodine deficiency (chiefly reduction of goitre and hypothyroidism—both too little and too much iodine can be bad for the thyroid), far outweigh the risks of iodine supplementation, although dosing must be handled with care.

One review concludes that most individuals suffer no disturbance from iodine excess, iodine-induced disturbances are mostly transient and easily managed, and that iodine-induced hyperthyroidism, in particular, disappears from the population within a few years of properly dosed iodine supplementation [57] .

Similarly, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects and safety of salt iodization [58] also concludes that benefits outweigh costs. The review finds that in certain contexts, iodization of salt at the population level may cause a transient increase in the incidence of hyperthyroidism (though not hypothyroidism). However, on the benefits side, evidence suggests that salt fortification causes moderate to low reductions in the incidence of goitre (moderate), cretinism (moderate), low cognitive function (low) and urinary iodine concentration (moderate). Based on this evidence a recent WHO report [59] strongly recommends that all salt be fortified with iodine as a safe and effective strategy to prevent and control iodine deficiency disorders for all populations.

Effect of Iodine on (mental) development in children

Iodine is crucial for normal physiological and cognitive growth and development of children [60] . A recent meta-analysis analyzed randomized controlled trials and found that iodine fortified foods are associated with increased urinary iodine concentration among children [61] . Another recent systematic review and meta-analysis looked at the effects of iodine supplementation on mental development of young children under 5 [62] . The authors concluded that evidence from recent studies suggests iodine-deficient children suffer a loss of 6.9-10.2 IQ points as compared with children who are not iodine-deficient. However, the authors caution that some study designs were weak and call for more research on the relation between iodized salt and mental development. Another recent cluster randomized trial investigated the effectiveness of iodized salt programs to improve mental development and physical growth in young children under 3. The trial found that the treatment group had higher scores on three out of four intelligence and motor tests. Although these results appear to provide support for the benefits of salt iodization programmes, it is worth noting that the study was funded by the Micronutrient Initiative, a non-profit agencies that works to eliminate vitamin and mineral deficiencies in developing countries, which may have biased the results [63] . Another recent natural experiment showed that in iodine-deficient regions of the United States in the 1920s, iodization raised IQ scores by 15 points and the average IQ in the United States by 3.5 points [64] .

A recent double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial compared direct iodine supplementation of infants versus supplementation of their breastfeeding mothers [65] . They found direct supplementation of infants to actually be less effective in improving infant iodine status than giving supplements to the mothers. This suggests that breastfeeding mothers pass on improved iodine status to their children. Will this effect generalize to salt iodization programmes in addition to direct supplementation? A systematic review examined iodine nutrition status among lactating mothers in countries with iodine fortification programmes (the review did not look at iodine status of the mother’s infants). The review concluded that although salt iodization is still the most feasible and cost effective approach for iodine deficiency control in pregnant and lactating mothers, iodine status in lactating mothers in most countries with voluntary programmes, but even in areas with mandatory iodine fortification is still within the iodine deficiency range, and so iodine supplementation in daily prenatal vitamin/ mineral supplements in lactating mothers is needed [66] . We assume that in the absence of daily prenatal iodine supplements, iodine fortification, which is also less costly as an intervention, will at least contribute to bettering the iodine status of mothers and their children. Similarly, another recent study from Turkey concluded even after 8 years after introduction of mandatory iodization programmes iodine intake is in pregnant women is still inadequate [67] .

Iodine loss due to storage and cooking

The iodine content of iodised table salt can decline over the course of long-term storage [68] . Givewell has voiced concern that there might be substantial loss of iodine in salt, which could potentially render the iodization ineffective [69] . We will now first review the evidence of the relative decrease in iodine content and whether a substantial amount of iodine remains, so that fortification programmes can adjust the absolute iodine content to take into account losses during storage.

One paper investigated this issue and concluded that iodine fortification is at least somewhat robust to storage. After 3.5 years of storage in sealed paper bags at room temperature in high humidity (30%–45%), the salt only lost 58.5% of its iodine content [70] . A more recent study looked at loss under higher humidity settings with unlimited airflow, which is perhaps a more realistic setting for a rural household [71] . The authors found that after 5 months of table salt storage in open jars at high humidity (90%), iodine losses rose to 70%. However, some storage procedures may mitigate these effects.

A study in Ethiopia investigated how this loss of iodine propagates through the supply chain from manufacturer to consumer. The study found that the concentration of iodine in the sampled salts decreased by 57% from the production site to the consumers. They concluded that due to iodine loss, 63% of adults, and 90% of pregnant women, were at risk of insufficient iodine intake. [72]

Food preparation can also affect iodine loss: one study found that, in the lab, after cooking table salt for 24 hours at 200°C, iodine loss was only 58.46% [73] . Another study looked at iodine content in different soups during cooking for 70 min at 100 degrees Celsius and found that bioavailability of iodine still fulfilled daily requirements [74] . Thus, as real-world cooking conditions in households are likely to be much more favourable, iodine loss during cooking should not be a concern.

The WHO advises that iodine losses under local conditions of production, climate, packaging and storage should be taken into account and additional amount of iodine should be added at factory level [75] . PHC has told [76] us that they take local storage and cooking conditions into account when determining fortification levels for iodine, as well as for other nutrients, particularly vitamin A. Specifically, PHC assesses current and local consumption and storage conditions either by conducting their own assessment, relying on data from the World Food Programme, or adapting ECSA (East, Central, and Southern Africa) fortification standards that are specifically tailored for regional consumption, cooking, and storage patterns.

Iron fortification

Iron-deficiency anaemia causes around 45 (31–65) million DALYs a year [77] . For comparison, malaria causes 83 million DALYs (63–110) [78] . Iron deficiency anaemia also makes up a major part of years lived with disability (YLD) in developing countries (see Figure 15).

Figure 15 : Overall “Years Lost due to Disability (YLD)” in developing countries. Iron deficiency anaemia is marked in black and makes up 6.76% of the total YLDs. Figure adapted with ‘Global Burden of Disease Compare tool’- see http://ihmeuw.org/3a5g . © 2013 University of Washington - Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (Global burden of Disease data 2010, released 3/2013)

Many trials that have looked into iron supplementation and fortification have documented improvements in hemoglobin status (and thus improvement of anaemia). A recent systematic review analysed data from 60 trials and concluded that food iron fortification resulted in a significant increase in hemoglobin (0.42 g/dl; 95% CI: 0.28, 0.56; P < 0.001) and serum ferritin but no effect on serum zinc concentrations, infections, physical growth and mental development [79] , [80] .

Because iron is important for development the effects of iron on children have been studied separately. Specifically, there have been four recent reviews and/or meta-analyses of RCTs that have investigated the effects of iron supplementation and fortification in children.

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the effects of iron-fortified foods on haemoglobin levels in children under 10 years of age, showed that intake of iron-fortified foods was associated with haemoglobin concentration [81] . The authors concluded that iron-fortified foods could be an effective in reducing iron deficiency anaemia in children.

Another systematic review examined 37 RCTs on iron supplementation in primary-school-aged children, and found evidence for improved haemoglobin response [82] .These results were congruent with findings of similar studies in adult populations [83] . Another, more recent systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs looking at the effects of daily iron supplementation in children in low- and middle-income settings similarly found that iron improved cognition, height, weight, iron deficiency and anaemia and is well-tolerated [84] . However, the evidence for effectiveness in younger children is less robust. A systematic review and meta-analysis examined randomised controlled trials of daily iron supplementation in 4–23 month-old children, and found evidence for , reduction of anaemia. The study concluded, however, that benefits for development of cognition, motor skills, height, and weight were uncertain [85] .

Do the effects of supplementation generalize to cheaper population-level fortification of staple foods interventions?

One very recent study evaluated the impact of Costa Rica's fortification program on anaemia in women and children [86] . Even though this was not a randomized controlled trial, the particularities of the data [87] strongly hint at a causal relationship between fortification and reduced anaemia . The results suggest that fortification markedly improved iron status and substantially reduced anaemia.

Another very recent study [88] used national-level surveys to conduct a cross country comparison of micronutrient fortification practices and anaemia rates in non-pregnant women. The authors suggest that, after controlling for confounding effects (such as level of development and endemic malaria), anaemia prevalence has decreased significantly in countries that fortify flour with micronutrients, while remaining unchanged in countries that do not, so that for each year of flour fortification anaemia prevalence is reduced by 2.4%, i.e. 2.4% fewer women are anemic [89] .

There are two separate systematic Cochrane reviews underway that summarize the evidence for potential benefits of flour fortification with iron against anaemia, one on maize flour fortification [90] and one on wheat flour fortification [91] . PHC conducts maize flour fortification in countries such as Malawi and wheat flour in countries such as Zimbabwe, so the results of these reviews will be interesting.

Does iron fortification increase malaria?

It has been hypothesized that elevated iron status can increase malaria risk in areas where malaria is endemic. This possibility is concerning for some of PHC’s projects, such as the iron fortification programme in Malawi, where malaria is endemic [92] , [93] . The hypothesis is biologically plausible, because the malaria parasite needs iron to function (indeed, it has been suggested that anemia might be an evolved response to fight malaria and other parasites) [94] . Studies of increased iron intake (via supplementation or fortification) in malaria-prone areas have yielded conflicting evidence on this question. We review findings from specific studies below, but whether increased iron intake increases malaria risk is a topic of ongoing research, and researchers call for greater study of the mechanisms underlying the negative effects of iron reported in some trials [95] .

One trial from Tanzania showed an increased risk of mortality among children after iron supplementation [96] . As a result, in 2006 the WHO changed its recommendations on iron supplementation for children in areas where malaria is endemic, from universal to targeted supplementation for iron-deficient children only [97] . .

However, a recent systematic C ochrane review from 2011 suggested that iron supplementation does not adversely affect children living in malaria‐endemic areas [98] and recommended that routine iron supplementation should not be withheld from children living in malaria-endemic countries. Another systematic review and meta-analysis from 2013 summarizing randomised controlled trials on the effect of daily iron supplementation on health in children [99] found no evidence that daily oral iron supplementation increased malaria, diarrhoea, or respiratory infection, but did identify evidence that iron increased fever (the authors note that however, that few studies were done in malaria-endemic areas or specifically reported malaria-related outcomes).

However, a more recent study from 2012 found that iron status predicts malaria risk in children [100] and another suggests that iron deficiency might protect against severe malaria and death in children [101] .

Another recent trial from 2013 did not find iron to increase the incidence of malaria among children in a malaria-endemic setting in which insecticide-treated bed nets were provided and appropriate malaria treatment was available [102] .

The most recent systematic review that we could find [103] suggests that overall, weighting positive and negative effects of iron, improving iron status reduces mortality risk similarly in children with malaria and in those without malaria [104] .

Given the conflicting evidence in the research literature, we have asked experts in this field for their opinion on whether iron fortification of wheat and maize flour in Malawi (as conducted by PHC) is on the whole harmful or beneficial. One such expert said that the question is currently unanswerable, but that most experts in the field would tend to assume that fortification will be safer than supplementation . The same expert noted, however, that this hypothesis is unproven and that research on the relative benefits and risks of fortification versus supplementation is ongoing. He concluded that, despite these uncertainties, he thinks it is fairly safe to assume that iron fortification is likely to be benign [105] . Another international expert suggested that the effects of iron fortification on malaria risk are not as well studied as those of iron supplementation, though an upcoming randomized controlled trial in Malawi should provide further evidence on the topic. The expert noted that that the risks associated with iron probably depends not only on the iron status of the host, but also on the manner/dose of giving the micronutrients [106] .

The WHO also suggests that conclusions from trials of iron supplementations risks should not be extrapolated to fortification or food-based approaches for delivering iron, where the patterns of iron absorption and metabolism may be substantially different [107] .

We have also asked PHC about this issue and they have reported that they are aware of the potential risks in malaria-prone areas, and are regularly consulting with national and international consultants (e.g. from the WHO) as well closely monitoring the current research on this topic and working with malaria prevention programmes on the ground.

In sum, we think that, placing more weight on expert opinion and the most systematic review that we could find, iron fortification is very likely to be beneficial as overall mortality and morbidity is reduced, even though there is some probability that it might increase malaria incidence or severity, however, this is effect is probably small.

Part 2

This report is broken into two parts.